1 Timothy 4:9-15

Hymn to the Theotokos

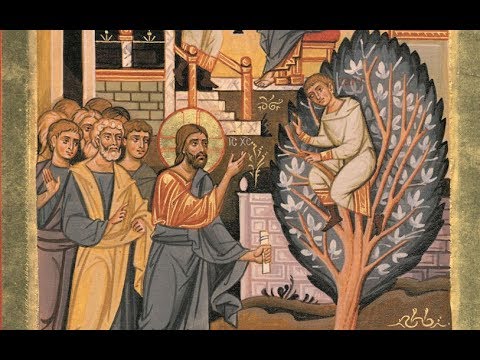

Luke 19:1-10

Many years ago, serving a psychiatric lock-down unit as a hospital chaplain, I would sometimes be called when patients had reached a high pitch of agitation. During these on-the-ledge conversations, I would ask, "What timezone is Heaven in?"

"What timezone is Heaven in?!" they might reply. "What does that mean?"

"Heaven's timezone is now. It is always now. The past no longer matters. The future is always a tangle of conflicting possibilities. All we have is now. Now is all there ever is."

For those of us who do not live on the edge of sanity, we might say reality, the insight of Heaven's now is no less important. The effects of rebellion against God in the Garden of Eden trace back to this loss — the loss of now. You see, time began ticking. Now slipped away. The perfect moment of day soon began to dim to darkest night. The fullness of the flower's bloom wilted as each petal collapsed from within, slowly but inescapably. With the loss of eternal now, the inexorable descent into death had begun.

It is the very nature of Heaven to be in the fullness of now. A holy sister who guided me during my seminary years would say, "We will be resurrected in all of our beauty ... whatever that might be for each us." Will we assume our former state as innocent children? Will we materialize once again as young adults in the prime of life? We will be resurrected in all of our beauty .... whatever that might mean." Anything that precedes or follows fullness is not perfect. Now. That is the ideal of Eden, of Heaven, and of all our hopes.

Last week, we reflected on the Greek word Μετανοει'τε (metanoeite), which means "Go back! Go back to the place where you made a wrong turn!" When St. Jerome translated this word for his Vulgate Bible nearly three hundred years later, he chose the phrase

| Poenitentiam agite, |

This is the spirit in which we should read our Gospel lesson this morning. For today is Zacchaeus Sunday, marking the beginning of our mental preparation for Great Lent. His Arabic name means pure or innocent. His physical stature is nearly childlike. We know something of his interior life, for he climbs a high sycamore — not the sort of thing adults do, but which children are drawn to.

Yet, entering his adult years, Zacchaeus took the wrong path. Growing up in occupied Palestine, he saw that young men have two primary career paths lying before them. They stand at the crossroads. On the one side we see a path leading to devout Jewish religious life, practicing the fine art of skirting Roman life wherever possible. To the other side is the path that embraces the Hellenized culture all around him, forgetting (or even hiding) Jewish identity.

We are too much taken in by Hollywood movies where some of the characters are dressed as Roman tribunes or procurators, some as soldiers, yet most wearing robes and drab gowns from central casting which we associate with the great mass of Jews of that period. The reality, though, was far different. The world all over the Eastern Mediterranean was a Greek world having a Greek culture. Just as in modern Israel today, only a minority of the people are devout religious Jews.

First-century Judeans, indeed most of the known world, had for generations grown up in a Hellenized world. If you should visit the Holy Land today, say Caesarea Maritima or the Cities of the Decapolis, you would think you had stumbled into the ruins of ancient Greece. Many of their cities were after the Greek classical style with beautiful arcaded agoras and Roman-Colosseum style arenas. The young men attended gymnasiums and engaged in Hellenic sports including what we would call Olympic events such as wrestling. Since their bodies were exposed — ancient Greek wrestling was practiced by nude athletes — their genitals would have been in full view.

This gave rise to a surprising fashion trend in first-century Judea — boys seeking to have their circumcisions surgically reversed. They wanted to be men of the world, not of back-water, dusty Palestine. Influential Jews wanted to hob nob with Roman society, made all the more accessible in a world which spoke Greek and which upheld ancient Greek and Roman values, which everybody knew. This helps us to understand the crossroads that boys encountered as they approached the age of adult life and career. Many wished to embrace their Roman citizenship (think of St. Paul's proud claim that he is a Roman citizen) and to become successful in Roman terms. One of these career paths was to become a member of the societas publicanorum, called publicans, whose duties included tax collection. Publicans entered the upper eschelon of Roman Society becoming Patricians of the Equestrian class, just below the Senatorial class.

By the time of Jesus, the stereotype of the hated tax collector had mostly receded. In previous times, the tax collector was little more than a "protection racket mobster". He competed with other men submitting bids to the Roman Senate. The most attractive bid granted a license to steal. He could demand any level of taxation he wanted so long as the Senate received their agreed-upon sum. In fact, the tax collector had to pay the year's taxes to the Senate up-front and then collect whatever he thought he could manage to extract from the people. (No limit!) Meantime, the Senate, having borrowed these monies from the tax collector, also paid him interest for what was, in effect, a loan. Opportunities for corruption were obvious pitting "collaborator" Judeans against their own families and friends. Moreover, publicans managed large public works projects, supplied needed materiale and provisions to the Roman Legions, and loaned money at high rates of interest. They lived in sumptuous villas, had ranks of servants, and entertained important Roman guests.

But Augustus Caesar, seeing this stinking hole of political corruption, drained the swamp. He instituted a flat tax of 1% levied against real property and income across the entire Empire. The days of the freewheeling publican were over. Two or three generations had passed before Jesus' three-year ministry following the Emperor's tax reforms. The publican continued to hold the social status of Equestrian class. He remained a high-visibility public servant. But as a tax collector, he was merely responsible for administrating a flat tax, which was well-known to all land owners and businessmen. Yes, he might collude with certain wealthy taxpayers to hide assets from the government (as people do today), but he was no longer the "arch fiend" figure of yesteryear.

Zacchaeus, therefore, might be seen as the boy who simply chose worldly life rather than godly life. Certainly, in the context of the secular business place, corruption is as old as business itself and will continue until end of the age. But in the life of one young man, something happens. With the heart of the spry boy he once was, he climbs a tree and gazes into the face of God, Who alone is good. Worldly success suddenly seems not so important. The callous that had covered his heart splits open revealing pink flesh, the heart-flesh of his childhood. All this the Lord of Life plainly sees and reads in Zaccaeus' character ... prompting Him to declare, "Zaccaeus, I will meet with you in your household today!" That is, He ratifies a meeting that has already occurred. What happens during this meeting? We might say, Nothing. Nothing happens, for it had already taken place and in a twinkling. Up in that tree, Zaccaeus, the boy-inside-the-man, went back. He went back to the place where he had gotten off track. He pledges that he will repay those he cheated and that he will sell half of everything he has and give it to the poor.

There was no counseling session, and there would be no schedule of suffering to expiate his moral guilt. There was only this: now. "Today," Jesus says, "salvation has come to this house." Salvation.

Today. Just do it. This is the message of the Lord Jesus:

| Metanoei'te! Go back to your own innocence! For the Kingdom of Heaven has drawn near. |