Hebrews 11:24-26-12:2

Troparion, Kontakion, etc.

John 1:43-51

|

"Truly, truly, I say to you, you will see Heaven opened ..."

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen. |

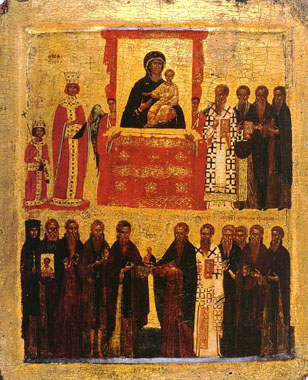

The Hermitage website normally offers weekly meditations as "pictures from the spiritual life." But today, as we celebrate the Seventh Ecumenical Council, which ended the persecution of Christians adoring icons, we ask a historical and intellectual question: why is it that the Western Church venerates statues but not (as a rule) icons, and the Eastern Church venerates icons, but not statues?

This is a striking fact of life for us. Our lifelong formation had been in the Western Church. We were surrounded by statues all our lives both in Roman Catholic and Anglo-Catholic churches. We prayed before them, venerated them, and received them as family heirlooms. In the Western Catholic Church, we rarely saw icons presented for veneration. Today, now becoming Orthodox religious, we never see statues in Orthodox churches. Why should this be?

St. Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain, the great commentator of the Ecumenical Councils, underlined this fact sharply:

|

As for ... statues, the catholic (Orthodox) Church not only does not adore them,

but she does not even manufacture them ... It may be said that ... this Council [The Seventh Ecumenical Council] is antagonistic to statues. |

In his commentaries, collectively titled The Rudder, which he offered in the eighteenth-century to steer and direct our understanding of the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church, he went on to say that

|

neither the letters written by patriarchs in their correspondence with one another, and to emperors,

nor the letters of Pope Gregory to Germanus and of Pope Adrian to the present Council, nor the speeches and orations which the bishops and monks made in connection with all eight Acts of the present Council said anything at all about statues or sculptured figures. (The Rudder, 414) |

As we have seen St. Nicodemus' commentary on the Seventh Council argues vigorously that statues are not icons. His main reason is as follows:

|

The reason and cause why statues are not adored or venerated ... seem to me to be the fact that when

they are handled and it is noticed that the whole body and all the members of the person or thing represented are contained in them and that they not only reveal the whole surface of it in three dimensions, but can even be felt in space, instead of merely appearing as such to the eye alone, they no longer appear to be, nor have they any longer any right to be called, icons or pictures, but on the contrary, they are sheer replications of the originals. Some persons, though, assert or opine that the reason why the Church rejected or did away with statues was in order to avoid entirely any likeness to idols. For the idols were statues of massive sculpture, capable of being felt on all sides with the hand and fingers. (The Rudder, 415) |

I would add that a statue is a highly complex geometrical object. Just imagine all the calculations that have be made to determine proportion and all the perspectives of the statue! These prodigious calculations carried out to achieve this imposing result call upon the mind of the observer who perceives the achievement. That is, any statue inevitably involves a rational transaction between the sculptor and those who survey his highly complex artwork. It is appropriate, therefore, that when philosophers and political leaders of the so-called Enlightenment (a revolution of anti-religion) wanted to exalt human reason, they did so by placing an enormous statue in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, entitled "Human Reason."

Who could deny that a statue is a work of art? Usually, religious sculpture is representational, attempting to depict a person. Again, this appeals to the mind, but not necessarily to the soul. By contrast, icons must be approached face to face. They are rarely representational calling not upon our minds but upon our souls. The great iconographer (and sculptor) Aidan Hart comments that

|

Sculptures are rooted in three dimensional space, while painted icons or relief works exist on surfaces,

such as walls, ceilings, or containers. For this reason, it could be argued, flat images can act more readily as windows to heaven. The fact that painting's two dimensionality is one step removed from three dimensional space enables them more readily to open onto heavenly space. (Hart, "Can Statuary Act As Icon?") |

That this particular difference — the intellectual vs. the spiritual — should cut emphatically across the nexus between the Western and Eastern Churches is a matter of historical fact. (As I have said, no statues in the East; in the West statues, but few icons.) And this should not surprise us, for the sensibilities of mathematics — the mental, the intellectual, the rational, — are quintessentially Roman. By contrast, the sensibilities of mystery — a sense of otherness, a stirring of the soul but not the mind — go to the heart of any Orthodox worship space. At the very least, Western worship is characterized by neat geometries of pews, aisles down the nave, and lines of perspective converging on a High Altar. By contrast, Orthodox worship space is non-linear with people standing amongst a cloud of witnesses who likewise appear in no regular pattern.

Again, no surprise, for the Roman Church emerges from the most tightly regulated civilization the world has ever known. Having seen so many Hollywood movies where Christians are fed to lions in the Roman Colosseum, we forget that Roman Catholicism from its beginnings was an aspect of and, later on, a leading expression of Roman culture. To understand the sensibilities of Roman worship, let us meditate, therefore, on the Roman mind and culture.

When we think of the Roman Empire and its legacy to world civilization, what are the first things that come to mind? Certainly, military science. The Roman Legions were the greatest military complex the world has ever known (in ratio to the world that was known to them). War colleges today continue to study Roman battles. Their neat phalanxes of legions, their mathematically calculated strategies and tactics, operated like a vast human machine.

Next, civil engineering carried out by the Romans surpassed all that had preceded it (by far!) and would not be matched again nearly until the modern period. Roman roads criss-crossing the world, aqueducts, and enormous and complex sewer systems survive to the present day. We can imagine the complex hydrodynamics that had to be handled by these systems. Roman sea walls made of concrete have only in the past few decades been deciphered. Even twentieth-century America could not unlock their secrets. As one measure of Roman genius, the rotunda dome of the Pantheon was constructed with matter-of-fact certitude by the Romans and then, after the fall of the Roman Empire, could not again be equaled, or even approximated, until the Renaissance. Century after century, various monarchs decreed that a Pantheon-like building would be constructed only to watch its flawed dome collapse — the sort of thing that gave rise to the phrase the "Dark Ages" as so much Roman knowledge had been lost for so many centuries following the descent of the Vandals and the Huns.

Next, we think of political science. The administrative genius of the Romans is a stupor mundi. The efficient governance of much of the known world for roughly a thousand years was among the greatest historical feats of human reason. The legal dimension of this achievement, taken in itself, ought to be considered a wonder of the world.

When the Roman Church was founded as an institution of the Empire, it was to be housed in basilicas, which were ancient Rome's judicial buildings. Again, these were not understood to be temples or churches. Rather, basilicas would have signified to every Roman citizen something else: the juridical, the civil, legalities. And the Roman Church would be founded upon an edifice of Canon Law at the insistence of the Emperor. To the present day, the Roman Church continues to be housed in basilicas, and to the present day, Canon Law dominates ecclesiastical, moral, and theological life. Just tune in to "Catholic Answers" on the radio or on the web, and it will not take long to discover that the Code of Canon Law and not theology constitute the life's blood of the Roman Church. Why is this? Why is that? Inevitably, Canon Law will decide most questions. As a professor of Roman Catholic theology, I strove to understand how Roman theology, Canon Law, and the Catechism were orthogonal to each other, but over the years of trying to square them to one other in a unity, I found that it could not be done. Canon Law and not theology is the rule of life in the Roman Church.

In sum, the Roman Empire, taken with its many institutions, was foremost a triumph of human reason. Engineering, in one form or another, was the foundation for Roman life and culture. And the Latin language was well suited to rational thought. It is a rigorous, highly particular, and well regulated language with its several declensions and conjugations. In that sense, it is an "engineered" language as few others could claim to be. Most important, while it possesses an active voice and passive voice (as English does), it lacks the middle voice of a language like Greek. That is, Latin does not have a special way to express mystery as Greek does. We may surmise that this subtle, non-rational mode of expression did not suit the engineering mind of the Romans.

In like measure, it should not surprise us that icons — those mysterious windows into Heaven, lacking proportion, lacking perspective, lacking geometric precision — did not suit the Roman taste. But statues? Oh yes! Romans executed statues with dazzling precision, achieving representational perfection, pleasing the intellect, and exalting human reason.

Do not expect the non-linear or the mysterious in Roman worship.

And

you will look in vain for a "Catholic Answers" anywhere in the world of Orthodoxy.

For the Orthodox prefer mystery

and

shrink in horror

from attempts to compass the Divine with human reason.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.