Mark 16:9-20 (Matins)

Romans 5:1-10

Matthew 6:22-33

|

"No one can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one and

love the other, or he will be devoted to the one and despise the other ... Seek ye first the Kingdom of God." In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen. |

A conversation that recurs at the Hermitage centers on a haunting mirror image: the unworldly Kingdom of God staring at an inverted picture, the unspiritual, irreligious City of Man. Each person has encountered these two images. For most people each is familiar and yet unfamiliar: the purity, sincerity, and deeply felt emotions of life in the Kingdom on one side and the clever, sophisticated, often arch world of city life on the other. Anyone who has been exposed (even for a few seconds) to "Saturday Night Live" on television or "Wait, Wait, Don't Tell Me" on Public Radio knows this distinctive way of life and thought.

We at the Hermitage are clear that the Kingdom of God represents the true image: understanding oneself to be a child of God and striving to follow our Exemplar on earth, Jesus, the Firstborn of Creation. The reversed, mirror image is the counterfeit. Its manner of superior sarcasm seems to promise meaningfulness. It seems to promise membership among those who "know better," who mock even the categories of purity and sincerity as being hopelessly naive. But, in fact, there is neither meaning nor membership, only thin tissues of nothing in an atmosphere of pretense.

It is strange that both of these outlooks on life should proceed from the same desire, which is the desire to "get to the bottom of things," to discard all cant and falsehood, to boil things down to their essences and to know them.

The spiritual mind seeks the true by rejecting worldly values, which Jesus (in our Gospel lesson this morning) calls "Mammon." In this language, attachment to worldly gain amounts to idolatry. During the Middle Ages, Mammon (a Hebrew word meaning "wealth") was promoted to be a demon god, and one of the Seven Princes of Hell, which in turn represented the Seven Deadly Sins. Through a process of synechdoche, then, Mammon suggests not only the compulsion for wealth but also for power, for lust, and for other unwholesome appetites.

The worldly mind also seeks the true but by a different method, which is scientism, whose element is the material world. That is, it posits that all things derive from matter, so a study of matter and its sub-microscopic components will lead to truth. It rejects God as a fantasy or a psychological projection. It affirms only matter, so "living well" and seeking materialistic goals are all that remain.

Consequently, the materialistic man and the spiritual man contemplate opposite understandings of time. The worldly man sees all change as being good because it leads to further discoveries in the material world. What is new is what is best, and perfection lies ahead.

The spiritual man understands that change all too often will lead to degradation of life. He sees perfection as having occurred in the past, in particular during the earthly life of Jesus of Nazareth, when God dwelt with man. The further one recedes from that golden time, in like measure, the more the future grows dim, as that golden goodness fades, is forgotten, and is lost.

Truly, these are mirror images, where one side is almost an opposite of the other. As Jesus warns in our Gospel lesson, one can never be reconciled with the other. To live in hope of this blended and reconciled life is to live in folly, even to point of danger. In the end, the uttermost conclusion of the world is life which is death, final and forever. The uttermost conclusion of the Kingdom is a death which is life, eternal and finally free of all worldliness.

Last week, we reflected on the twentieth-century vocation of our Church, the Russian Orthodox Church, which was plunged into the furnace of tyrannical, Christ-hating worldliness. Sadly, this tyranny and violence has come to dominate our own era in the United States and the Americanized world in general. Even the Churches we have known through our twentieth-century lives have become dominated by this culture, to the point where Christian doctrine is attacked, labeled "hate speech," and criminalized.

Where is the devout Christian to go? What is he or she to do? In the English-speaking world, the instinct to go back to ones beginnings, to the earliest and purest examples of Christian life, will lead us back to our forebears, the Celtic saints.

How far back into the early and authentic Christian lifeworld will the Celts lead us? Archaeologists have discovered their monasteries built on the Atlantic coast of Ireland and Scotland from the 300s A.D. That is, these Celtic monastics were celebrating the Eucharist and contemplating God during the same years that St. Anthony of the Desert was receiving St. Athanasius to his hermitage in Egypt.

But monasteries are merely what archaeologists have unearthed thus far. Meantime, linguistics scholars studying the migration of language groups and scientists studying chromosomes have suggested that these Celtic Christians can be traced back to the Apostolic Age, known as "the Galatians" to St. Paul, who evangelized them.

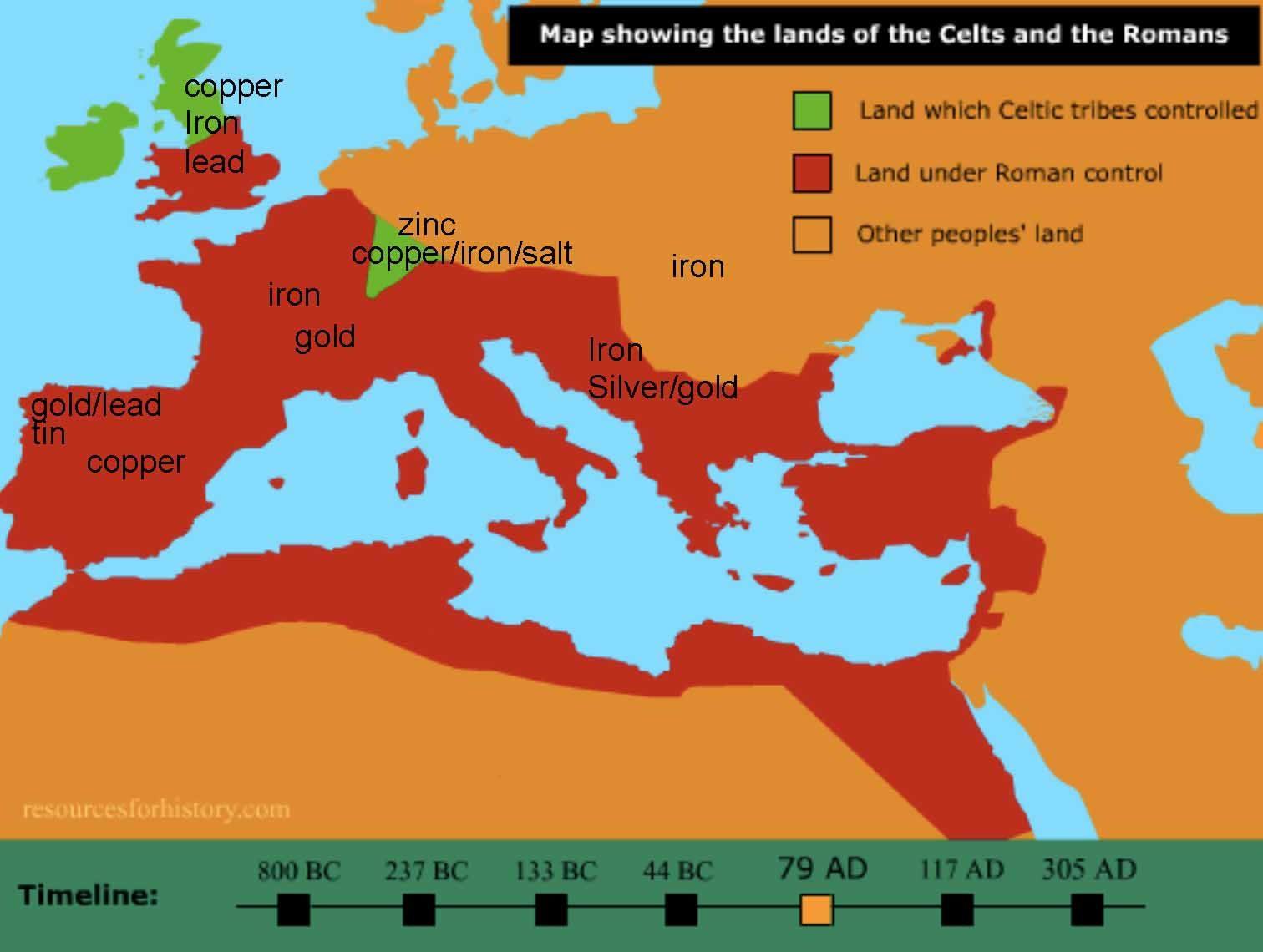

Jesus' brief homily this morning on the two opposing "masters" reminds us that the heart of Christianity is essentially an other-worldly, even an anti-worldly, heart. As one early example, St. Paul's response upon encountering the Lord Jesus was to retreat into the Arabian wilderness for three years (following the forty-day pattern of Jesus Himself). In his missionary journeys, he then urged others to shun the world and the "prince of the air" (Eph 2:2). And this the Galatians did. Avoiding the hated Roman Legions, they camped to the north of Rome, where St. Paul ministered to them. They then migrated along the north shore of the Mediterranean skirting Gaul and thence into the Iberian peninsula (modern-day Spain) sailing "beyond the world" through the Pillars of Hercules (Gibraltar). They settled on the west coast of Ireland and then on to Scotland.

One of Scotland's "sacred texts," the Declaration of Arbroath asserts that their forebears "journeyed from Greater Scythia by way of ... the Pillars of Hercules." Current genetic evidence suggests that these people indeed migrated from Scythia, from the shores of the Black Sea, which is why Scotland's national flag bears the Cross of St. Andrew, the "first Apostle" of Orthodoxy, who planted a cross on a hill in Kiev and predicted many golden-domed churches for the people of Holy 'Rus.

The Gaelic-speaking (Goidelic) Celts gave a wide berth to the English Channel and to Britain itself,

as Roman galleys were plying these waters

and

Roman authorities

were

governing this land south of Hadrian's Wall

(with Scotland to the north).

Rome confined its primary activities to southeast England,

away from the Brythonic-Celtic-speaking lands of Cornwall and Wales.

The Gaelic-speaking (Goidelic) Celts gave a wide berth to the English Channel and to Britain itself,

as Roman galleys were plying these waters

and

Roman authorities

were

governing this land south of Hadrian's Wall

(with Scotland to the north).

Rome confined its primary activities to southeast England,

away from the Brythonic-Celtic-speaking lands of Cornwall and Wales.

Popular myths depict missionaries like St. Patrick bringing Christianity to these western lands. But that is not quite right. Christianity, but not Roman Christianity, had been lived here, devoutly and authentically, centuries before St. Patrick. We must remember that by the time of St. Patrick, Christianity had been tolerated and then promoted for more than a hundred years in the Roman Empire.

The true picture of Christian life in the British Isles was one of a (now) native Christianity, evangelized by St. Andrew and then St. Paul, which later competed with the "Italian religion" of the Romans. As the Romans sent their military Legions throughout Britain, so they also sent their religious legions, in particular, the Benedictine Order of monks, such as Bede, the publicist who rendered English history in a Roman slant, and much later the Italian Anselmo, who would become an Archbishop of Canterbury.

This centuries-long struggle was between a pure, Apostolic Christianity, preserved as in amber in the isolation of Ireland and Scotland, and a Roman Catholicism rooted in European cities, representing the worldly aspirations of empire and power. As the Roman military machine sought to dominate and rule the world, so popes like Gregory the Great, sent out legions of missionaries, working in lock-step with their military counterparts, to impose Italian liturgies and doctrines everywhere Rome ruled. This mania for absolute uniformity, suppressing local liturgies (which could be traced back to the Apostles), would become its imperial trademark and theme.

As a sidelight the popes we knew as children and young adults had names like Eugenio Pacelli, Giovanni Montini, and Angelo Roncalli. When the Pole Karol Wojtyla was elected, the Roman Catholic world was shocked, for popes had always been Italian (last exception four hundred years earlier) as the Roman religion was always an Italian religion.

This antagonism between authentic Apostolic Christianity

and

the hegemony of Italian religion

took on new significance

when the

Roman Catholic Church decided to break off

from the ancient and universal Catholic Church

in order to establish its own identity and empire,

enacting a Great Schism in 1054.

This antagonism between authentic Apostolic Christianity

and

the hegemony of Italian religion

took on new significance

when the

Roman Catholic Church decided to break off

from the ancient and universal Catholic Church

in order to establish its own identity and empire,

enacting a Great Schism in 1054.

Meantime, people of the British Isles, speaking Anglo-Saxon (a Germanic language) in England and Celtic in Cornwall, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland, lived on as a distant, Apostolic lifeworld from its Italian and French-speaking neighbors in Europe.

A dozen years later in 1066, a French-speaking army flying the banner of the Italian pontiff, Anselmo of Baggio (created Pope Alexander II), invaded Britain in a so-called "holy war" conquering that land westward to the Welsh borderlands and then setting in place overlords who did not know the native languages. The result would be one of history's greatest genocides, erasing an entire lifeworld, culture, and faith, and rendering those who survived as a permanent underclass. French would be spoken by all free men and women, while Anglo-Saxon would be spoken by the servants and slaves. (I say "slaves," but these included the gentry and aristocracy who had become slaves.)

For the Christian who seeks these early forebears,

evangelized by St. Andrew and St. Paul and carrying their beliefs and patterns of worship with them,

the task is daunting.

The Roman missionaries destroyed all signs of Christian life they encountered.

As late as 1078 the French bishop of Salisbury held Celtic-Anglo-Saxon

liturgies in his hands and began revising them.

Five centuries later Anglicans looked to these materials,

know as the Sarum Rite,

as their best hope of recovering pre-Italian Catholic worship materials.

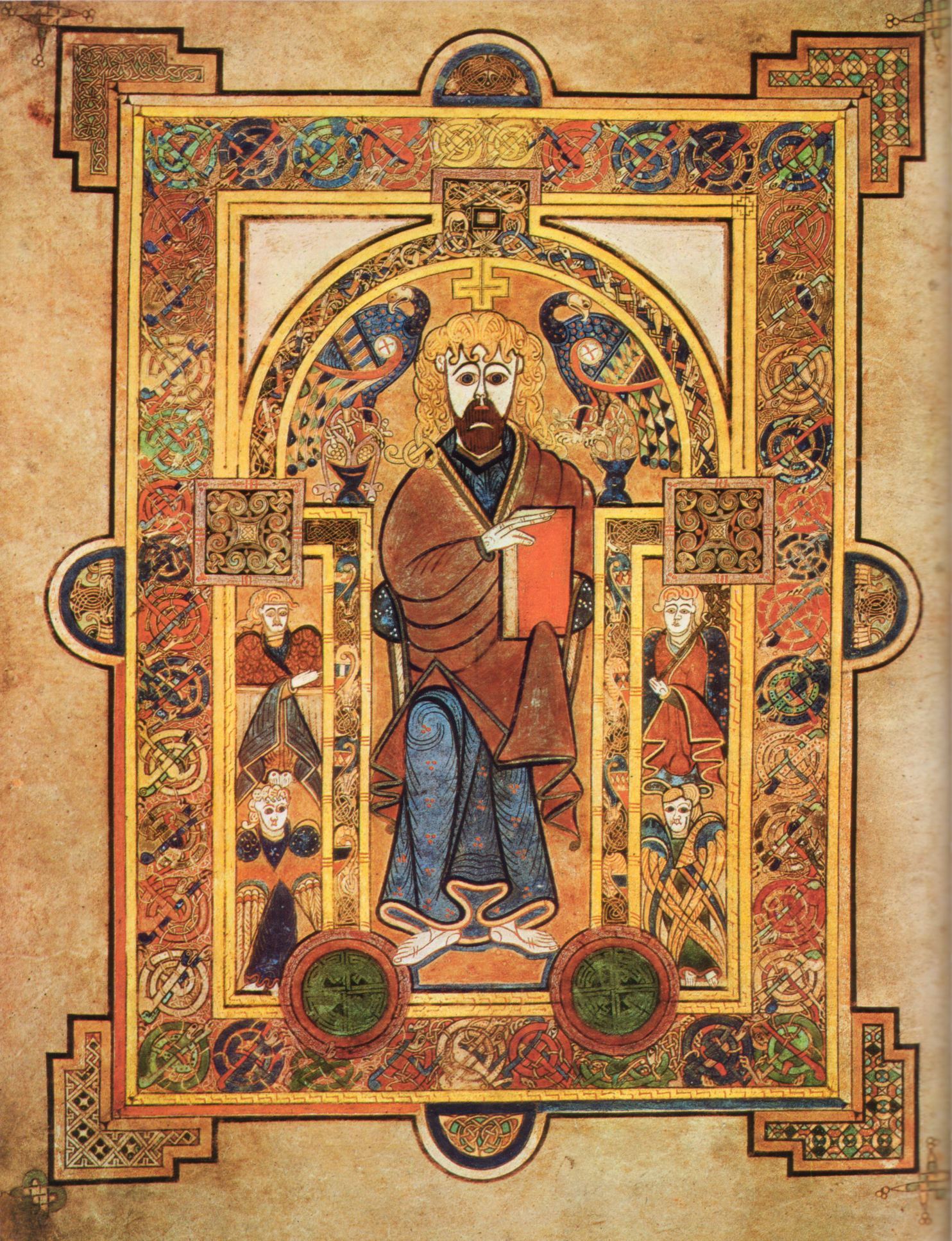

What could not be erased from the hearts of these faithful Christians was their passion for icons. Unlike Italian religion, which is given over to the veneration of statues, the Celts brought their ancient culture with them to Ireland and Scotland continuing the traditions of the Apostles who evangelized them (and we recall that the first great icon painter was St. Luke). The Book of Kells from the late eighth century is the most brilliant example of their iconography. But this collection stands prominently among many in an extensive, centuries-old catalogue that has become synonymous with Celtic culture. Icons are carved even into their magnificent and imposing crosses, eschewing the Italian tradition of the crucifix corpus.

A charism of the Hermitage of Our Lady of the Angels (named by Metropolitan Hilarion, a Primate of the Russian Orthodox Church and First Hierarch of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia) is devotion to this ideal of the Catholic and Apostolic Church, eluding the Roman influence as our Goidelic Celt ancestors did. Like them we also have sought to live on the edge of the earth (our island is a most remote locale from any major land mass). We have sought to live on the edge of time (we are one of the last stops before you reach the International Date Line). And like St. Andrew and St. Paul we live by the calendar that Jesus observed (presently thirteen days behind the world from which we have retreated).

People wonder why we have become Russian Orthodox. But they do not know the story of Christianity. They do not know that the Scythians are now called the Russians. And they do not realize that these same stalwart people braved every kind of hazard and privation in order to be faithful to the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Faith, putting worldly ways and the Roman Empire behind them.

We who have lived as Catholics all our lives (Anglo-Catholic and Roman Catholic)

have sought what we understand to be faithful and true.

The world may see in us an erratic, even indecisive, pattern.

But we have not veered from our course.

We have sailed beyond the known world

through the Pillars of Hercules,

in a sense,

discovering where we had begun

—

to our own beginnings and to our own story.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.