|

And He said to them, "I saw Satan fall like lightning

from heaven. Behold, I give you the authority ..." In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen. |

Today we celebrate Michaelmas. As a religious community of the Western Church, we relished this feast as "St. Michael and All Angels" on September 29 of the Gregorian Calendar. In the Orthodox Church it is called the Synaxis of the Archangel St. Michael and the Other Bodiless Powers. I perceive that the word angel, meaning "messenger" in the Greek, is used with a sense of special handling in the Orthodox Church. For a messenger implies an "emissary," one that is "sent out" from one kingdom to another. That is, the word angel emphasizes distance, a definite "there" vs. "here."

"Bodiless power" does not imply any of these things. In fact, it invokes a clause from the Creed: "and of all things visible and invisible." Invisible insists on here. Something at a distant you cannot see. In that case, visible and invisible make no difference. Its twin term in the Creed is visible. There is no elsewhere in this clause but rather what we see here and what we do not see here.

And this broaches the subject of our reflection this morning: Is Heaven "here" or "there"? Our answer to this question will reveal much about how we picture our salvation .... and how to get there, to Heaven. Being a Western Catholic all my life, I used to laugh .... and then, later in life, wonder at Clarence Oddbody, AS2 (Angel Second-class). He is the angel appearing in Frank Capra's classic film, It's a Wonderful Life. Clarence, you see, is a deceased man who at death became an angel but after 200 years still had not earned his wings. Wait a second, I would think, isn't Frank Capra Roman Catholic? Surely, he does not believe that people become angels when they die! Angels are an altogether different life form, a different species in the created order. But I was also aware that much Baroque painting featured little angels whose faces were those of children who had died (this period coincided with the Second Great Plague, which swept through Spain, Northern Europe, and England). I had chalked this up to artistic freedom and to the obligations that come with the patronage system. But perhaps in my Western arrogance, I had failed in my reverence for the Divine things.

The Orthodox tradition constantly reminds us of the vast unity that is God. Orthodoxy seems innately suspicious of hierarchies, division markers, and taxonomies, which we find in Western theology. And this is right, for, as we considered last week with Jesus' ministry to the Lost Tribe of Gad, God's own nature is unity:

| Hear! O hear, Israel! The Lord thy God is One. (Deut 6:4) |

Our master subject is holiness. God is holy and seeks to be united to all the holy things He has made. Each thing was good at its creation. The intelligent creatures who have sought evil, bodiless powers and humans, cannot be united to Him, for this would be to pollute holiness. The Kingdom of Heaven is, above all, good.

The bodiless powers by tradition are made on the First Day of Creation. They are part of that Light, which God brought into being with His primal, elemental utterance. (here in an ancient Latin rendering):

|

Deus dixit, "Fiat lux et lux fiat."

God said, "Let there be light, and light there was." |

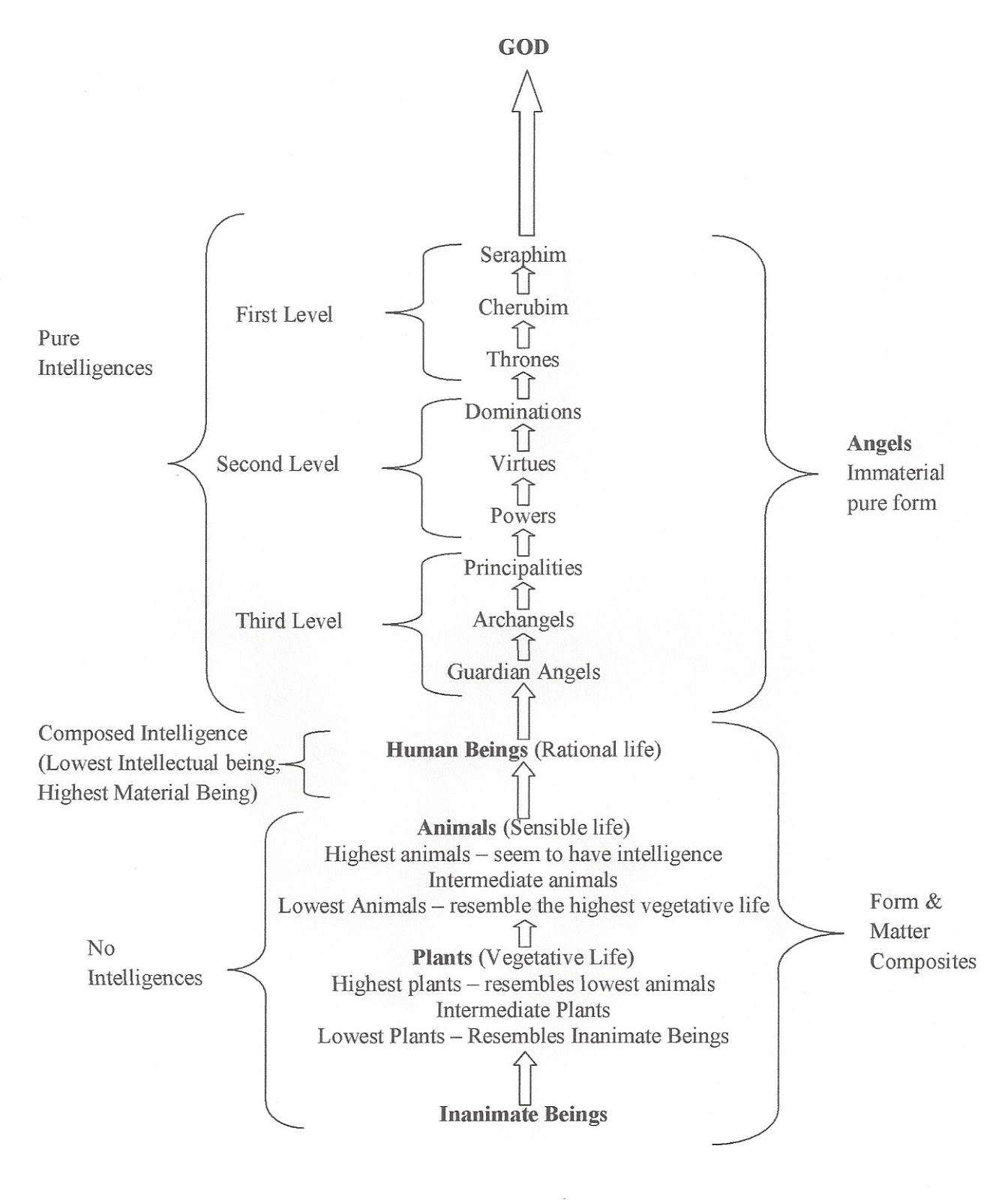

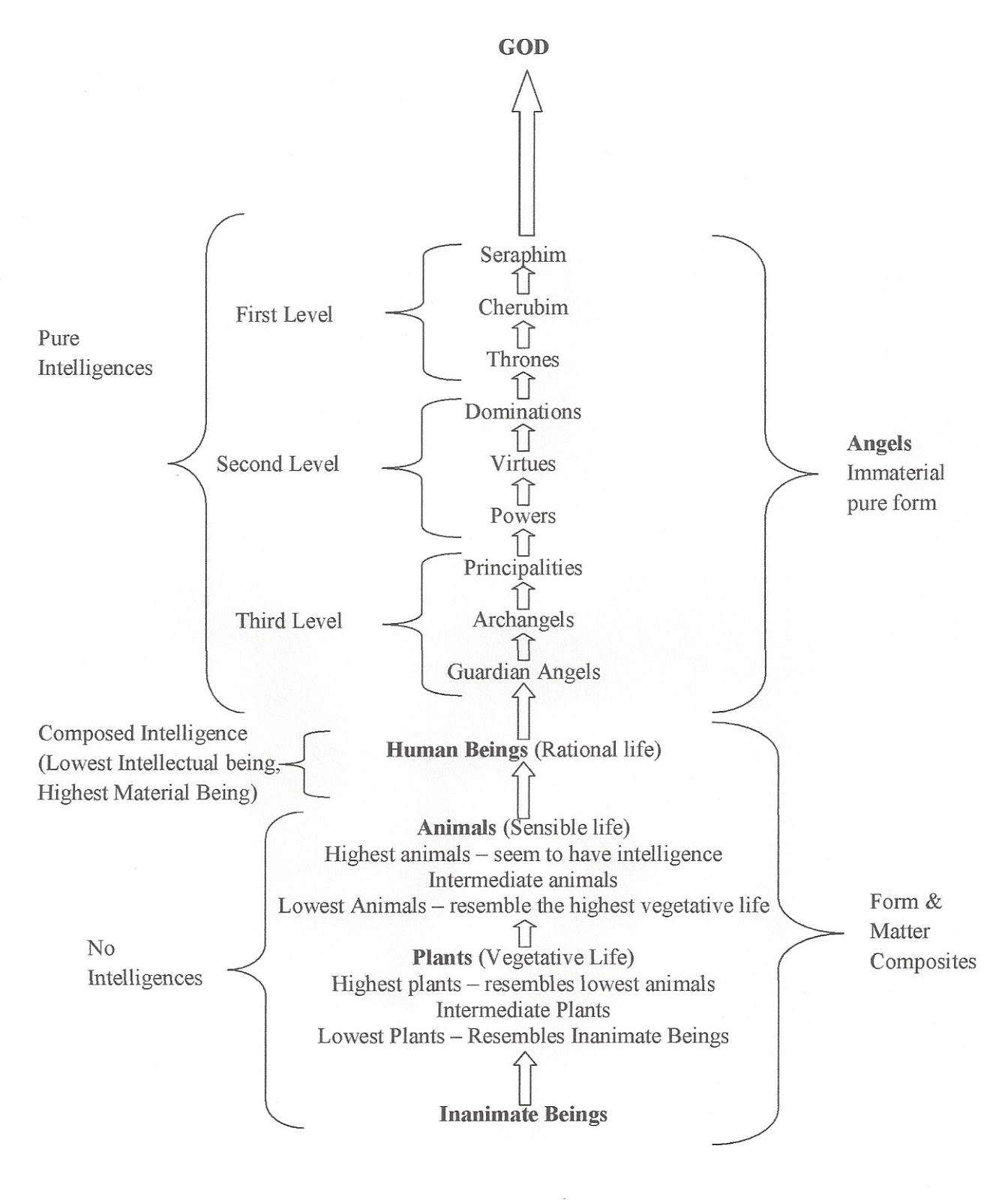

According to the fifth-century Neo-Platonic philosopher, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, there are nine choirs of angels (De Coelesti Hierarchia). Nonetheless, Orthodox tradition emphasizes that this individuation is a function of our brokenness. Angels became apparent in Eden only after the Fall, not before it. Individuation is the result of division, not unity. Eden was the image of perfect harmony with God: pure Holiness, All-in-all, ultimate unity-in-goodness.

The Greek philosopher, Aristotle, Plato's student, was very fond of hierarchies

and

sought to anatomize the world,

physical and metaphysical,

with his technology of division and subdivision.

At the time the Roman Church broke off from

the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church,

establishing its own, separate institution,

Aristotelian philosophy dominated the minds of her theologians.

(Some people say this a cause for the Schism.)

In retrospect,

their writings,

known today as Scholastic Philosophy,

"insist[ed] upon the mechanics of science rather than on an intellectual grasp of reality"

(New Catholic Encyclopedia).

The result was a religion that went to extremes in the related directions of rationalism and legalism.

The Roman Catholic saint, Thomas Aquinas, was the leading expositor of Scholasticism and focused much of his attention on angels, to the point where he became known as "the Angelic Doctor." The university named for him in Rome in called "the Angelicum."

So, here we have a thumbnail sketch of Greek philosophical influences concerning the Western understanding of angels. But what of the Hebrew traditions? What role did they play? The simple answer comes down to a question: "Which canon of the Bible do you choose?" You know, we might discuss the formation of the New Testament canon for hours. This challenge would be sorted out and decided by the Orthodox Fathers with considerable influence being exerted in the fourth century by St. Athanasius. But Christians did not decide the canon of Hebrew Scripture. Rabbis did that. We simply received their canon.

I say Rabbis because at the destruction of the Jewish lifeworld around 70 A.D., it would be the Rabbinic tradition, the new face of the Pharisees, who would decide which books would become the canon of the Hebrew Bible. The name Pharisee was so closely linked to the Jewish rebellion and to its leadership, that the name was suppressed, eschewed by its own party, so as to elude Roman persecution following the calamity. But the Mishnah, the earliest record of Rabbinic writings, clearly valorizes Pharisaic opinions above all others. These Rabbis are the Pharisees.

What then happened to the other Jewish parties? What of the Zealots, Sadducees, and Essenes, whose names have survived down to our day? The commitments of the Zealots were fundamentally political, but their polis, their city and nation, had disappeared. The Sadducees were the aristocratic, ruling class, but following the destruction of Judea, nothing remained to rule.

The last group, the Essenes, are known to us through the first-century Roman-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus

|

For three forms of philosophy are pursued among the Judeans: the members

of one are Pharisees, of another Sadducees, and the third [school], who certainly are reputed to cultivate seriousness, are called Essenes .... (The Jewish War, 8.3) |

Through the writings of St. Paul, himself a former Pharisee, we have come to know the Pharisaic school as being highly legalistic, whose vocation was to debate minutia of the Law. Their antagonism toward the Lord Jesus and His followers is amply recorded in the Holy Gospels.

The Essenes have become better known to us in our own time. Thanks to a series of discoveries (1946-47, 1956), their writings found near the northwest shore of the Dead Sea, have revealed a school nearly opposite the Pharisees. Theirs was a highly spiritual expression of Judaism, no doubt rebuffed and marginalized by Pharisees and Sadducees. Because they prized humility, seeking neither influence nor power, they have followed a low profile through the annals of history.

Such that we can piece out the Essene canon of Scripture, we find that it includes works we recognize from the Hebrew Bible. But it also includes works not selected for the canon of Scripture by the Pharisees, such as the Temple Scroll, a work emphasizing sanctification as the path toward union with God, and the Book of Enoch. This latter work has special significance for Christians, for it mentions a "Son of Man"

|

.... although Judeans by ancestry, they are even more mutually affectionate than the

others [Sadducees and Pharisees]. Whereas these men shun the pleasures as vice, they consider self-control and not succumbing to the passions virtue.... Since [they are] despisers of wealth — their communal stock is astonishing — one cannot find a person among them who has more in terms of possessions. For by a law, those coming into the school must yield up their funds to the order, with the result that in all [their ranks] neither the humiliation of poverty nor the superiority of wealth is detectable, but the assets of each one have been mixed in together, as if they were brothers, to create one fund for all. (Ibid, 8.4) |

In this Rabbinic — Essene opposition, we are tempted to exaggerate to make a point:

Certainly,

both parties were Jews,

so these oppositions are not black-and-white.

Surely, both honored the ritual of sacrifice.

The question is,

which heart and mind do your bring to the Altar of sacrifice?

Certainly,

both parties were Jews,

so these oppositions are not black-and-white.

Surely, both honored the ritual of sacrifice.

The question is,

which heart and mind do your bring to the Altar of sacrifice?

Consider the scene at the Altar of Incense within the Temple: Zechariah encounters the Archangel Gabriel. He behaves exactly as we would expect a Sadducee or Pharisee to behave, leaping directly into intellectual debate: "How shall I know this?" he asks sharply. He cannot see that the presence of a bodiless power by its nature is an invitation to go beyond rationalism into inner, spiritual depths.

After all, sacrifice and the Law were subjects which received reverence among the Lord Jesus and His followers. We are summoned, therefore, to consider the spiritual dimension of sacrifice. We recall Psalm 51,

|

The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit,

A broken and a contrite heart — These, O God, You will not despise. (Ps 51:17) |

|

"For assuredly, I say to you, till Heaven and earth pass away, one jot or one tittle

will by no means pass from the Law till all is fulfilled." (Mt 5:18). |

| "It is expedient for us that one man should die for the people, and not that the whole nation should perish." (Jn 18:14) |

But an Essene, I believe, would hear it differently. What does it mean "to fulfill the Law"? The Law is fulfilled when God's people become blameless in His sight, a royal priesthood, an holy nation (as St. Peter suggested). For what is justice? In the first century, a just person is one whose life is perfectly attuned to the holy ways of God. And what is righteousness? A righteous person is one found to be blameless in a court of the Law. That is, union with God is not accomplished merely through animal sacrifice:

| "For it is not possible that the blood of bulls and goats could take away sins." (Heb 10:4) |

So, which is our Heaven? Is it a far-off destination to which we gain entrance by means of offering up the Lord Jesus in sacrifice? This would be to accept Caiaphas' formulation: offering Jesus up to appease Caesar for the sake of the people. Or is Heaven all around us — here, now, invisible, "always already" (to borrow a technical term from philosophy)? Do we ride a train in the trance of worldly distraction until we arrive to Heaven's city gate or do we see it more and more clearly each day through a process of personal sanctification?

In like measure, let us ask a second question: which is our conception of the bodiless powers? Are they messengers or emissaries from a distant kingdom? Or are they mysteriously part of a vast unity of light, which is God, a unity into which we are invited as Zacherias was within the Temple?

You know, The Jewish lifeworld, from the time of Abraham to the end of the Second Temple era in the first century, saw no distinction between God and angels. After all, how many of us today venerate an icon of the Holy Trinity depicting Three Angels sitting with Abraham (Genesis 18:1-15). Consider Psalm 8, which St. Paul quoted at length today in our Epistle lesson:

|

What is man that You are mindful of him,

And the son of man that You visit him? For You have made him a little lower than the angels ... (Ps 8:4-5) |

Jesus and the Apostles were not troubled by categories like "canon of Scripture."

That is our preoccupation.

As we study the origins of the Septuagint (among other subjects),

we find that the Jewish lifeworld,

whether in Jerusalem

or

in the great Jewish center of learning at Alexandria,

was highly diverse politically, linguistically, culturally, academically, and religiously.

Among these groups,

the Essenes leap out to us as the school closest to our own thinking and values as Orthodox Christians.

As it happens (here on Michaelmas) their cherished text, the Book of Enoch, opens to us a fuller and more detailed understanding of the bodiless powers. In it we find not hierarchy but rather unity radiating from God embracing the holy creatures He seeks to be united to Him or, sadly, the loss of this unity — pure spiritual creatures devolving into their lower, animal state.

An example of the former are the bodiless powers of light, whom we perceive to be angels. An example of the latter is ourselves. We are the example of the pure creatures of light who devolved into our animal nature .... at the Fall. That is, we were once part of this unity in Eden, a light-filled and holy estate. By rejecting God, we instantly brought shadows onto that light. In a twinkling, the harmony and unity of Eden was fragmented, as we detect division between Adam and Eve when their sin is discovered. (Adam tells God, "The woman You gave me. She did it.")

Whether we survey the whole of human history or the span of a single lifetime, we see that this is the human story wherein we either descend down into animality, becoming all body and passions, or we ascend higher and higher toward Heaven in our longing for holiness becoming all soul (though mysteriously retaining our bodily form).

This same freedom of choice also belongs to the bodiless powers. In the Book of Enoch, we learn of angels who entertain feelings of lust as they gaze upon the daughters of men. Giving free reign to these human, even animal, urges, their latent bodily nature awakens within them, and they are able to have intercourse with the daughters of Eve. The spawn of these unions are called Nephilim, sometimes translated giants. The Epistle of St. Jude makes mention of them:

|

And the angels who did not keep their proper domain, but left their

own abode, He has reserved in everlasting chains under darkness for the judgment of the great day. (Jude 6) |

The Scriptures, both New Testament and Old Testament, sound this theme over and over. We may attach ourselves to the world, represented by the glittering city, Ur of the Chaldees, or we may depart from it as Abraham had done seeking a wilderness, seeking God. Alternatively, we may fasten ourselves to the love of God and of each other keeping His commandments and following in His holy ways. Only a fool or one stubborn in perversity could fail to hear this Heavenly strain — not brought to us by emissaries or messengers, but echoing down into the depths of our inner life from the time of our conception and birth. And if we should choose to ignore it, the Lord Jesus in His mercy has deigned to articulate it plainly. Of the world He says,

| "I do not pray for the world." (Jn 17:9) |

|

In this world ye shall have tribulation, but be of good cheer,

I have overcome the world." (Jn 16:33) |

| And He said to them, "I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven. Behold, I give you the authority ..." |