Luke 24:1-12 (Matins)

Acts 9:32-42

John 5:1-15

"Sin No More"

"Sin no more, lest a worse thing come upon you."

(Jn 5:14)

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

The modern mind is indignant:

"Blame a paralytic for his paralysis?!

What is this?!"

But we must go slow.

We must understand these deep and distant backgrounds (such that we can),

and

reflect.

Reflection is a vocation which God enjoins upon each of us,

an office of love.

For who can claim to be faithful in love

who

does not contemplate the Beloved at all times and in all places?

We must avoid a two-dimensional view of Jesus as healer.

Gospel depictions can leave us with a sense of a clinic waiting room

packed with undifferentiated diseases and their sufferers.

Without question,

multitudes pursued the Lord Jesus seeking to touch even the hem of His garment:

Then great multitudes came to Him, having with them the lame, blind, mute, maimed,

and many others; and they laid them down at Jesus' feet, and He healed them.

(Mt 15:30)

|

Yet, disease and death are much more than the occasion for Jesus' miracles.

They are the occasion for the Incarnation of God.

God's Person did not touch the human lifeworld with His Own Body and His Own Blood

in order to inaugurate a healing ministry.

After all,

every person whom Jesus healed from disease later declined again.

Every person whom Jesus raised from the dead died again.

Healing, then, cannot be the reason for Jesus' mission to our world.

Disease and death are defining marks of the human condition.

Everyone born into the world begins a journey toward death.

When I received a terminal diagnosis in 1995,

it came to me

with

blinding clarity that I had always known this.

We are all riding a train bound for death.

We do not know which stop will be ours.

It turned out that my stop was coming a little earlier than I had anticipated.

This was no great revelation;

in fact,

it was a rather small nuance in detail.

I had been dying all along.

But I had failed to own this fact

together with the rather pedestrian question of when.

This is our universal condition.

And this is what God sees as He surveys the Earth.

We might exclaim,

"But it's a matter of life and death!"

Yet for God death is no great matter.

Death is not even its own subject

but

rather

a moment between two subjects:

worldly life and the greater life

beside which our earthly journey is merely preparation ....

and

a microscopically brief one at that.

Even atheists

can be sure of life after death.

In the post-CPR era,

we all have read accounts of after-death experiences.

We know to a certainty

that the earthly journey does not end in the insensate grave and nothingness.

The human is the only creature God made to be permanent

and

the only one having capacity for holiness.

The question is not whether but where.

Will it be eternal life with God in His marvelous Heaven of goodness and light?

Or

will it be an eternal divorce from God and all goodness?

This is the great subject for which the Father sent His Son into the world.

This morning's Gospel lesson is brief,

fifteen verses,

but here is laid out much of what God's sees of the human condition

and

the subject for the Son's Incarnation.

Our drama plays out at an Asklepion .... what we would call a spa or sanatorium,

examples of which were scattered throughout the ancient world.

Archaelologists have discovered more than three hundred in Greece alone.

The Pergamon Asklepion was among the most important

along with the spas

of Epidarius and Kos,

established more than ten centuries before the birth of Christ.

Continuing into the Roman era,

these

sanatoriums played a central role in daily life.

Each was a temple

—

a center of worship of

and

animal sacrifice for

the god Asklepios,

as well as being a clinic,

where physicians saw patients.

You may scoff at my word clinic,

but we shouldn't.

In some respects,

the practice of medicine in the first century was not so different from medicine

practiced in the early twentieth century.

The Dean of the Yale Medical School,

Lewis Thomas,

wrote that

medicine practiced in 1940

had more in common with

Hippocrates and Galen

than

with medicine practiced following the antibiotics revolution

(The Youngest Science, 1983).

Galen performed cataract surgery.

Pliny the Elder wrote that an ancestor of Gaius Julius Caesar

"was so named, from his having been cut from his mother's womb"

(Historia naturalis, 77-79 A.D.)

—

that is,

caesar, from the Latin caedera, "to cut."

Today we say, "Caesarian Section."

Physicians lanced boils.

They discovered effective medicinal properties of barks, roots, herbs, and clay,

some of which we still use today.

They soaked infections in hot water.

Galen understood the importance of a clean operating theater

though the germ theory was still a long ways off.

Nonetheless,

every Roman physician and patient seem to have prayed to

Asklepios for success.

The depiction of the Bethesda pool posted at the top of this reflection

is based on ruins found in Jerusalem today.

It is nearly identical to the Asklepion at Kos (also posted with this reflection):

the stairs leading down into the waters

and

the porticoes or porches built around the temple,

where the sick took shelter from the weather.

People who did experience healing

made offerings to the god Asklepios in the form of body parts

—

say, an ear or leg in a sculpted or bronze-cast representation.

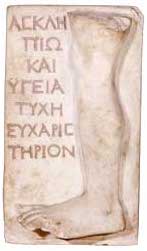

The leg sculpture posted with today's reflection was presented to an Asklepion during Jesus lifetime.

The Greek inscription reads,

"a thank-offering to Asklepios and Hygeia" (Greek goddess of good health).

In addition to these offerings,

blood from animals was offered,

similar to sacrificial rites practiced throughout the ancient world

and

certainly dating back to seventh century B.C. Babylon,

where

the Hebrew elite underwent transformation during a long exile.

King Nebuchadnezzar II,

who had conquered Judea,

makes his first appearance in the

surviving historical record as a faithful prince overseeing

the restoration of the Temple of Marduk, the Mesopotamian god

(Britannica, "Nebuchadnezzar II").

Later, upon ascending the throne,

Nebuchadnezzar boasted that Marduk had never eaten so well,

helping us to understand the centrality of animal sacrifice in Babylonian culture

and

its inevitable influence on the Hebrews, who spent nearly four generations there.

Nearly four generations.

Think of your own family.

Can anyone remember a lifeworld four generations ago?

This is some of our background as

Jesus and His entourage enter the scene.

We may picture the Lord standing at the top of the stone staircase

surveying all that is happening.

He sees the disturbance of waters spurring strong men to push aside the vulnerable

(for the people believed it was only the freshly stirred waters which could heal).

Among the weakest is a paralytic man who has languished on

the Asklepion steps for thirty-eight years.

We strain to find a starker example of dog-pack-think in the Gospels than this one.

By tradition an angel of God sanctified the waters for purposes of healing

but once a year (Troparion for Sunday of the Paralytic, Pentecostarion),

touching off a frantic contest to be first.

And we well understand God's perspective as He takes in this frantic scene.

What is illness, what even is death, compared to the vast and endless

Kingdom of Heaven and its imperatives?

Is it not better to practice Heavenly virtues

and

come to the succor of this paralyzed man

than to enter a fracas trampling down others?

And what if one should reach the water first and actually be healed?

What is that?

For at his core the "healed" man is still a snarling animal

and

no company for God.

Jesus also sees the inevitable parallels posed by this scene:

people offering each other in sacrifice to the pagan god Asklepios

and

then later sending Asklepios their own body parts as a thank-offering (albeit in the form of sculpture).

Only three chapters earlier,

Jesus had overturned stacks of dove cages in the Zion Temple

because the holiness of the Temple had devolved into the coarse bargain

—

of blood for salvation:

|

And He said to those who sold doves, "Take these things away! Do not make My Father's

house a house of merchandise!"

(Jn 2:16)

|

The Greek word here, by the way, is not merchandise.

The phrase is house of trade:

οικον εμφοριον,

(oikon emphorion).

And what is being traded?

The rites of theosis or sanctification

have

devolved into a swap of blood-sacrifice for salvation.

Far from becoming sanctified,

these men,

in effect,

sacrifice the lives of their neighbors in exchange for their own hoped-for healing:

"Not you! But me!"

All of this helps us gain perspective on the prominent place of healing in Jesus'

ministry.

God alone is the Lord of Life.

As a troparion we read this morning attested,

Jesus healed great multitudes

by instituting the healing waters of Baptism.

He is the Lord both of our animate life on Earth

and

unending life beyond the Earth.

The excesses to which God's people have gone in the direction of blood-sacrifice,

however,

is a subject that echoes through the Gospels,

rising to a climax with Jesus words,

|

"[I will] destroy this Temple ...."

(Jn 2:19)

|

Consider the meditation on blood-sacrifice

placed before us in the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

A wounded man on the Jericho Road

(which by the way is a road covered with jagged and sharp rocks)

lies bleeding.

This causes a Levite and a priest to give him a wide berth.

Why?

Because they fear becoming ritually unclean

as they contemplate standing before the altar of sacrifice.

This raises a basic question concerning salvation:

Which will save you?

Blood-sacrifice in the Zion Temple or personal sanctity expressed in compassion?

After all,

the question which occasioned

the Good Samaritan parable in the first place is this one:

|

"Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?"

(Lu 10:25)

|

Jesus' answer, "Love thy neighbor," points us back to the waters of the Asklepion.

The cult of Asklepios with its symbol of the caduceus,

the serpent entwined upon a rod (which we find in our medical culture today),

is an old one

dating back

at least to fourth-century B.C. Babylon.

And, of course, we have the example

of Moses' rod with a bronze serpent entwined upon it (Num 21:9).

Remember?

In the Book of Numbers,

he holds the rod with the serpent aloft in the wilderness to heal.

Yet we find in the Holy Scriptures

concerning the wholesomeness of such symbols controversy.

In 2 Kings we read that King Hezekiah

|

removed the high places and broke the sacred pillars,

cut down the wooden image and broke in pieces the bronze serpent that Moses had made;

for until those days the children of Israel burned incense to it,

and called it Nehushtan. He trusted in the Lord God of Israel,

so that after him was none like him among all the kings of Judah, nor who were before him.

(2 Kings 18:4-5)

|

This brief passage attests a very important principle:

the kings of Israel did not hesitate to revise Scriptural principles.

In this light,

we must reflect on another Scriptural conflict:

the tension between personal sanctification in religious rites versus blood-sacrifice in religious rites.

"To what purpose is the multitude of your sacrifices to Me?"

Says the Lord.

"I have had enough of burnt offerings of rams

And the fat of fed cattle.

I do not delight in the blood of bulls,

Or of lambs or goats."

(Isa 1:11)

|

And again

.... do not sin.

Meditate within your heart on your bed, and be still. Selah

Offer the sacrifices of righteousness,

And put your trust in the Lord.

(Ps 4:4-5)

|

And again

Sacrifice and offering You did not desire;

My ears You have opened.

Burnt offering and sin offering You did not require.

(Ps 40:6)

|

And again

The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit, A broken and a contrite heart —

These, O God, You will not despise.

(Ps 51:17)

|

Yet, the Torah undeniably includes instructions (placed in God's mouth) for blood-sacrifice.

What can this mean?

Is it possible that the Torah was revised during the Babylonian Captivity?

In the words of Yehezkel Kaufmann

of the Hebrew University, Jerusalem,

|

The exile is the watershed. With the exile, the religion of Israel

comes to an end, and Judaism begins.

|

Before the exile, the Hebrew people.

After the exile, the Jews

—

two separate and different lifeworlds.

The Hebrew religion of personal sanctification

practiced in the First Temple

is

replaced by a post-exilic Jewish religion of blood-sacrifice,

a legacy of Babylon.

This is the view ascending among many scholars (including Metropolitans of the Orthodox Church).

And this helps us to understand the origins of our own Orthodox worship and especially theosis.

As

recent scholarship in now bringing to light,

the long tradition of worship to God,

going back to the First Temple,

lies in conforming our inborn Image of God to the ways of Heaven.

This is life!

As our brief lesson concludes,

Jesus quotes Psalm 4 to the paralytic:

For the sacrifices acceptable to God are a clean heart and a right spirit.

Sin no more:

leave off worship to Asklepios;

leave off animal sacrifice in hopes for long life.

For I desire mercy and not sacrifice,

And the knowledge of God more than burnt offerings.

(Hosea 6:6)

|

Take heart, O Christian.

For the way to Heaven is not so hard to discern.

Know God.

Pray to Him.

Speak to Him.

Above all, trust Him.

And follow His holy ways

that you ascend to the everlasting climes of Heaven.

The Lord be with you!

And also with everyone,

for this is His will.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.

Amen.