Mark 16:1-8 (Matins)

1 Corinthians 6:12-20

Luke 15:11-32

Prodigal

Son, you are always with Me, and all that I have is yours.

(Lu 15:31)

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

Mention the word parable,

and

most people will think of two right away:

the Good Samaritan

and

the Prodigal Son.

It is easy to understand why the Parable of the Good Samaritan

should instantly come to mind.

On the surface,

it is the exaltation of decency and compassion

over callousness and selfishness.

The Parable of the Prodigal Son is cherished no less.

In fact,

it is hard to think of a scene from any parable more widely commemorated in art

than this one.

We find it painted down through the centuries and all over the world.

We think of the famous works of many:

of the Spanish painter Murillo,

the French painter Tissue,

the English painter Swan,

the Dutch masters Rubens and Rembrandt,

Albrecht Durer,

Gustave Doré

and

down to the artists of our period,

such as the Missouri native, George Lightfoot,

who depicts the father receiving his drug-shattered, hippie son

beneath his hands of blessing,

while while his other son,

a successful business executive,

probably working in St. Louis,

disapproves.

The catalogue of paintings bearing this title

must run into the hundreds.

Certainly,

the themes in this brief tale run deep.

It is a story of second chances,

of patient understanding,

and,

first among these,

of unconditional love.

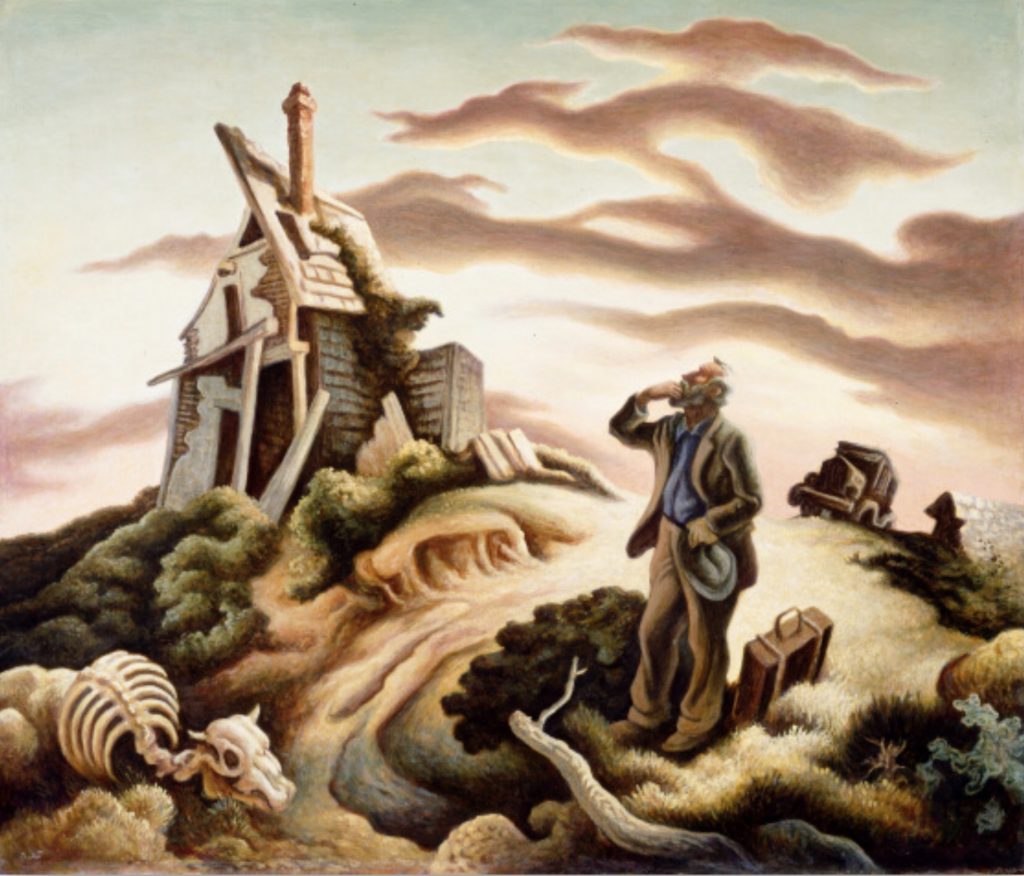

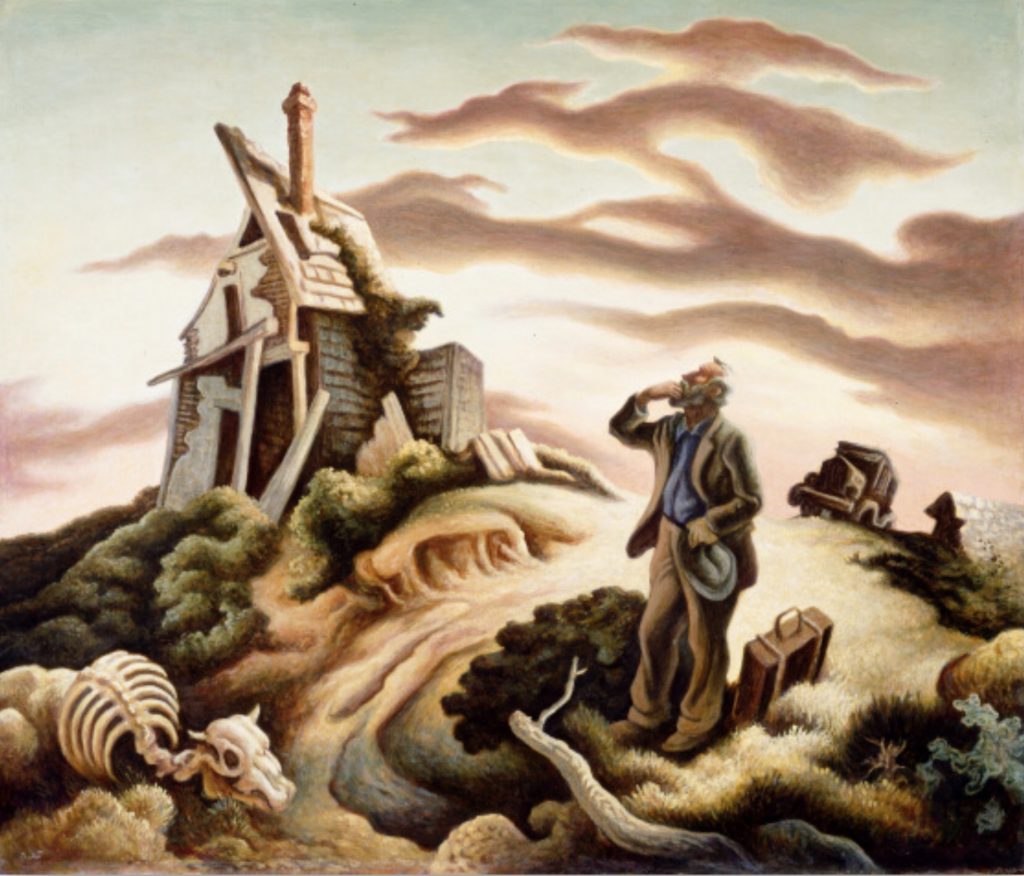

Perhaps no painter has depicted the depths of this love,

this self-sacrificing love,

more fully than the American artist

Thomas Hart Benton

in his painting entitled "Prodigal Son"

(which we have posted on our website).

For Benton grasps something that eludes many others:

the Parable of the Prodigal Son

is a tale of general ruin,

not only for the younger son,

who squanders his inheritance and defiles himself unto shameful degradation,

but this misadventure is also ruinous to his father and his brother.

For their entire estate

—

their world, their livelihood

—

has been gutted:

|

"He divided to them his livelihood."

(Lu 15:12)

|

After all,

there is a reason why estates are bequeathed only after the owner has died,

for a farm (or a business) is usually not viable after it has been divided

and

certainly not viable after it has been dissolved.

This important premise

—

that he gave to the younger son fully half the estate

—

would of course be the nominal case.

The father has two heirs.

The younger son has demanded fully his half:

|

"Father, give me the portion of goods that falls to me."

|

that is,

all that he would have seen at the bequest following his father's death.

The father confirms this stark fact when he tells the older son, "All that I have is yours."

Literally, half the estate is now gone;

all the father has, all that remains in his hands, is the older son's portion.

I know people have read this passage figuratively:

"All that I have is yours" meaning "Mi casa es su casa."

First,

it is doubtful that our North American idioms go back more than a couple of hundred years.

More to the point,

this reading

would make no sense in the case of a father speaking to the son who grew up on this estate.

Hearing this would, indeed, be cold comfort to the son,

who took his family's hospitality for granted .... as we all rightly do.

Do your parents need to tell you that you are welcome in their home?

If they do, then something must be wrong.

No,

let us stop

and

hear the father's words in hard, practical tones:

"All that I have is yours."

That is, "All that remains is your half."

"Do not fear that you have been cheated of your half, son.

It is still safely in hands."

In Benton's painting,

the younger son returns to his father's farm.

Perhaps he has served a prison term

and

finally has been released.

We do not know.

All that we can see is that his clothes are rumpled,

he's an older man;

his belongings fit into one suitcase;

and

he drives an old farm truck.

But whatever the case may be,

he stands outside the ancestral home

and

beholds .... a general ruin:

the house has collapsed in on itself from neglect;

all the livestock deprived of food and water reduced to skeletal form.

Everyone is gone

—

a once thriving farm laid waste.

And he stands in the foreground,

with his hat in his hand

and

gasps holding his hand to his mouth.

He takes in the full measure of what his prodigality has cost his family,

which is everything.

Is this so hard to imagine?

If so,

then you have never been part of a broken family

—

a family gored by the destructive conduct of even one member.

Consider the promiscuous mother,

the notorious mother in the neighborhood.

Do the other mothers in town send their children to her house for milk and cookies?

Consider the alcoholic father.

In his train are a whole raft of bitter memories:

ruined wedding receptions,

spoiled Christmas celebrations,

tearful birthdays.

And then there is the brother or sister lost in the world of opioids,

covered with tattoos, body-piercings, and living in utter degradation

as they connive to steal anything that is not nailed down.

Is it not so that

their brokenness strikes at the heart of their whole family?

For this is the nature of love, especially family love.

Either we are "all in" or we are not.

Or to say it from a different direction,

we are all in this together.

The idea that our sins affect no one but ourselves is a fiction

designed only to assuage only our own consciences.

There is no such thing as victimless crime,

for

each act of evil stains the world all round it,

and

especially the family.

In this,

we grasp what the sin of Eden has meant for everyone in the family.

The Christian faith is fundamentally family.

Our God is known as Father.

How remarkable!

The only claim we have to His wonderful Heaven

is that we are adopted sons and daughters.

Eden is the story of our mother,

who blighted the family with a grievous act of treachery.

And our father foolishly bowed down submissively to her impulsive nature:

"Well, I guess if you're going to go that way, I'll go, too."

You know,

our Church does not accept this premise of "bad seed,"

no more than a virtuous daughter could be forever stained by her mother's adulteries.

No, that is not it.

And so-called Original Sin

was an innovation of fifth-century invented by a Latin Father,

hatched as a justification for his own promiscuity, which was extreme, and alcoholism.

"Well, you see, I was born this way.

Really, I'm the victim."

In any case,

the Protestant theologians, and especially John Calvin,

made this a centerpiece of Protestant belief,

and

it has hugely influenced our culture of victimhood:

"You see none of it is our fault.

We are all born this way."

Let us think about this in real terms.

If the story of the Prodigal Son played out in our own neighborhoods,

would not all the neighbors rush to the conclusion that the younger son

suffers from medical conditions?

Would they not point out that he suffers from alcoholism.

He has diseases:

substance-abuse addition,

gambling addiction

sex addition.

And it is not far-fetched to imagine that soon a therapist

would enter the story assigning

all blame on the father,

who failed him as a parent,

and

the older brother,

who oppressed him.

"It is not fault.

It is theirs!"

But the choices we make in life are just that:

our choices.

We decide.

We decide for goodness,

or

we decide to cooperate with evil,

throwing open the gates.

You see,

evil is an objective power in the world

before it becomes subjective through our consent.

It is out there,

having no part in us ....

until we invite it into our souls

and

make it the central and most imposing feature of our lives and personalities,

the thing for which we become best known

and

the place where our thoughts go all the time.

Knowing a foremost professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School,

I did not miss my opportunity to ask him point blank,

"What is the difference between mad and bad?

At what stage of mental illness are we no longer responsible for our actions?

When do we shade from being a perpetrator to becoming a victim?"

His reply was just as direct:

"If you know what you are doing,

say, that you have chosen to sleep with someone else's wife,

then you are fully responsible for all your actions."

"So, anything short of full-blown psychosis

replete with hallucinations presenting a false reality

causing the world around us to become unintelligible ....

other than in that extreme case,

we are the deciders."

"I'm afraid so," he said.

Why should this sad, sad tale of a prodigal son,

this chronicle of personal degradation and family ruin,

be so popular?

It speaks powerfully to us

in every century and in every country around the world

because its themes run so deep ....

all the way back to Eden?

It is a synopsis of much Holy Scripture.

St. Irenaeus,

a spiritual grandson of St. John the Theologian

(he was ordained by Polycarp),

explained that Adam and Eve had been born as children

and

that their sin was the willful foolishness we often see in adolescents.

Irenaeus says that,

in essence,

the sin of our first parents was impatience.

For they would have inherited everything anyway,

including the hidden things of God, which the serpent hints at.

But, you see, Eve wanted it now,

betraying Father God

and

ruining paradise ....

goring the father, destroying the farm ....

just as the Prodigal Son could not wait,

injuring everyone around him.

As Father God is both Mother-Father to His children in Eden

and to us,

the Prodigal's father

is also

both mother and a father.

He is the family patriarch, but

he is also the figure of patience,

understanding,

and

compassion.

He is gentle.

Rembrandt captures this dual quality by depicting the father's right hand

as that of a woman and his left hand as the that of a man

(also posted with the reflection).

And the father of the parable teaches us something essential about the qualities of our God

and,

therefore,

of our relationship with Him.

He trusts us completely.

The Psalmist writes that High Heaven belongs to Him,

but the earth He has given to us (Ps 115:16).

It is all in our hands.

He will not vitiate that gift by taking it back into His more able hands

whenever things seem to be going off the rails.

If He has decided to trust us,

then He will

trust us to the end.

Like the father of our tale,

He does not wrest control back into His hands,

for that

would violate the nature of our relationship with Him.

Yes,

He loves us unconditionally.

But He cannot bless everything we do with His supernatural blessing.

People who have separated themselves from God

will ask me why the wonderful things happening to those people over there

are not happening to them .... after they have placed themselves out of the reach

of Divine blessing.

But we ought not blame Him for the so-called misfortunes we have visited upon ourselves.

He will not chase after us with a magic wand

or

even give His angels charge over us.

If we have parted ways with Him,

then we have parted ways.

The choice has been ours.

Our own guardian angel, therefore, is powerless to push back against our worst impulses and choices.

Do we not see this every day?

We are the sovereigns of our decisions.

Notice that the father does not follow the son into brothels and gambling dens and bar rooms.

He does not pick his son up as he lays in the mud

fighting off swine to eat their hay-corns.

If this is the life he has made,

then

so be it.

When St. Paul writes,

|

.... nor height nor depth, nor any other created thing, shall be able

to separate us from the love of God which is in Christ Jesus

our Lord.

(Rom 8:39)

|

he does not mean that God will follow us into our every degradation with His Holy Presence.

To borrow C. S. Lewis' conception,

God is not an old grandfather with a great, white beard who just wants everyone to be happy

(Letters to Malcolm, 1964).

No,

the sense in which

we cannot be separated from the love of God is something quite different:

He will always be there, very present to us, as soon as we turn to Him.

As soon as we turn our hearts to Him,

He is already there.

We do not have to look Him up

or

find His present address.

We do not have to phone Him or write a letter to ask if He will see us.

He will be right there .... instantly, attentively, desiring to enfold us in His loving arms ....

at the very moment that our heart breaks,

and

we are ready to make a change of life.

In the Holy Apostles Convent translation we read this morning,

we find, "He came to himself."

In this, the father of the prodigal waiting at the road side,

looking for the appearance of a figure in the distance,

ever vigilant for the return of his son,

is the very image of our God.

Another layer of our Parable this morning reveals

an irony of the holy life

depicted in the lives of the older brother and younger brother.

The older brother is the picture of steady, humble, faithfulness.

We see him at work.

He is a dutiful son.

He seems to be working late while others attend a party.

His is the path of the nun or the monk:

asking nothing, giving all, and drawing no attention to himself.

We might say he presents holy life:

the journey of a lifetime seeking intimacy with God.

Meantime,

his younger brother has entered into the very special communion with God

which he seeks,

but

he gets there right aways!

After all,

as the Psalmist promises,

what faster way to enter the most intimate place with God

than

turning to Him in our brokenheartedness?

And we think of Henri Nouwen

well-known exegesis:

that the parable represents the classic phases of conversion.

We begin as the younger son,

experiencing our "breakthrough moment."

We then become the monk or religious brother or pilgrim,

represented by the older son,

who sometimes becomes impatient with novices or worldly people.

And

finally we mature into the father:

patient, loving, understanding, willing to offer sacrificial love

even to the point of his own ruin,

that is, crucifixion.

Finally,

the Parable of the Prodigal Son reveals a most deep mystery,

which is

God's emptying of Himself

(kénosis)

so that He might live as one of us.

Similarly,

the father in the parable permits his own high stature and estate to be reduced

to the shallow dimensions of the younger son's impulses.

Certainly, we are right to reverence the Passion of the Lord Jesus.

We wince, we weep, to see Him

ill-received,

mocked,

spitted on,

scourged,

and

crucified.

These scenes rend our hearts and extort our tears.

Who does not weep here at this Hermitage on Good Friday?

But these vivid red colors must fade when set beside the self-emptying of God

in order

to enter the horrible straits of our narrow humanity.

Imagine your being stuffed into a very small box .... for three decades,

except that God began by being the most expansive Being in the universe.

And He has done this,

suffering nearly total self-annihilation

patiently, compassionately, and faithfully.

If the younger son of our parable has "ruined everything,"

then consider Our Lord Jesus,

Who set aside an incomprehensible glory

in order to be born into mud and dung

only to be marginalized and mocked

—

first as "Son of Mary" (Mk 6:3) suggesting illegitimacy

and

openly insulting His Mother;

then condemned as a mad man by His own family (Lu 8:35);

and

finally

to be arrayed in purple

by scoffing thugs (Mk 15:17ff),

who blindfold Him

and

beat Him

challenging Him to prophesy.

To say the least, His own received Him not" (Jn 1:11).

Yes,

Jesus permitted everything to be ruined .... nearly silently

as the father of His parable would.

Truly,

the figure of the father standing at a roadside

is not so far from the compassionate, forgiving Lord nailed to the Cross.

"Behold all who pass by. Never was sorrow like mine."

And as Jesus gives to us,

who failed Him so miserably,

the gift of eternal life,

so the father

will kill the fatted calf,

will exalt the returned son with a robe,

and

will adorn him with a costly ring.

Yes, the mystery of God's jealous love,

of His single-minded zeal for our welfare,

of His willingness to give away everything dear,

even His Only-begotten Son,

that He might

more perfectly,

love us,

who have betrayed Him.

This is deepest of all earthly mysteries

to be found in this mysterious parable.

In this brief tale of twenty, short verses,

we shall enter a labyrinth.

And

not least among its twisting byways is

the haunting tale of a self-destructive son,

which turns out to be

the poignant history of the world

and

the heart-breaking depiction of

all our disappointed hopes and dreams.

Yet does God stand at a roadside,

covered with the degradation we have poured on Him.

For our story is not the story of a faithful people.

It is the story a faithful God .... unfailing, loving, perfect.

In the Name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.

Amen.