This was our theme the First Sunday of the Great Fast: the harbinger of light, Holy Mary, enters the claybound world of benighted, even demonic, faith.

On our first Sunday of our pilgrimage, we sojourned at the Second Temple. We contemplated a most brilliant presence of light and grace entering the heavy walls of a stone tomb: the temple, which was a slaughterhouse, where the bodies of animals were vainly offered in an imagined trade as blood for salvation. Do we imagine that a tower to Heaven might ascend from a pile of dead goats? Do we accept that offerings made to demons like Babylon's Marduk or to Persia's Mithra might secure salvation for the people Israel? After all, the Second Temple at its inauguration was patterned on the "animal sacrifice" spirituality of Mesopotamia, who underwrote the construction and supervised over it.

Now, lest my words cause scandal, may I pause here to reassure? The Hebrew faith life of the Levant was not the monolithic Judaism that we had come to perceive in recent centuries. It was a diverse collection of many patterns of historic Hebrew belief. The evidence for this has always been right before us. Do not the Scriptures themselves describe idolatry of Baal and then later Mesopotamian gods (we would say, demons) as being a chronic problem? Does not the Torah depict a "stiff-necked people" who will not follow God's ways? Demonstrably, the people Israel entertained many thoughts and inevitably drifted into many beliefs. This is what our Scriptures reveal to us.

As one leading example, the Essenes of the first century A.D. (who closely resemble Early Christians) having a population on par with Sadducees or Pharisees and living throughout every village of historic Israel, did not offer animal sacrifices at the Temple. To cite their contemporary Philo,

|

They have shown themselves especially devout in the service of God, not

by offering sacrifices of animals, but by resolving to sanctify their minds. (Quod Omnis, 75) |

Sounds like St. Paul, doesn't it?

Moreover, the Jews who fled to Elephantine following the Return from Babylon did not offer animal sacrifice in their Egyptian temple. (Bezalel Porten, Archives of Elephantine (Berkeley, 1968). And, of course, a group from the historic Northern Kingdom dear to our own hearts, Jesus of Nazareth and His followers, did not practice animal sacrifice. Indeed, the Master made a whip of cords and drove the men who sold these animals out of the Second Temple. He cried out that they were transforming His Father's house into a scheme for trade (Greek oikon emphorion), that is, blood traded for salvation. He will mock this proposition of a trade in his Parable of the Good Samaritan, in which a priest and a Levite leave a gravely injured man on the ground bleeding lest they violate Temple ritual related to sacrifice. "Which is more important," Jesus asks? "Blood ritual or moral virtue and a pure heart?"

You know, these are Sunday school basics.

Oh yes, the heavy clay and stone of the Second Temple nearly suffocate. Yet, our spirits soared to behold the tender Theotokos as the spirit of new breath and new life ascending its steps. She will be the dwelling place for the Lord of light. Her Nativity at the Vernal Equinox pointed back to the morning of the world in Eden. For God crafted the universe itself upon the lives of His Holy Ones. Who could dispute that the created universe is secondary to God's Son, the Uncreated Logos? .... as one notable example.

This was our theme the First Sunday of the Great Fast:

the harbinger of light,

Holy Mary,

enters the claybound world of benighted, even demonic, faith.

On our Second Sunday, the Holy Spirit bids us return to this meditation. The figure before us is not Holy Mary but a middle-aged woman, who Jesus names "daughter of Abraham," a phrase unknown in the Scriptures until this moment. For the subject is her Heavenly ascent .... and ours. This is the fitting invitation on the Second Sunday of the Fast, that we take a sober look at ourselves, drawing courage from a three-year-old girl who entered the massive clay and stone around her. For now is our task — to ascend to God's grace and light from the heavy clay in which we also have enclosed ourselves.

It is surely no surprise to learn that this theme, which is the kernel of all our earthly journeys, should be developed in several parallel places across the Gospels. The Lord Jesus has lain it before His Disciples (and the world) at a most holy site of the Hebrew lifeworld: Shechem, near the ancient Temple on Mount Gerizim in Samaria.

As He and His followers approach Jacob's Well, He encounters a different daughter of Abraham. The Samaritan Woman at the Well knows the path of clay. She knows it very well. Over many years, sexual appetite has propeled her forward each day. This has been her story through many husbands, suggesting serial adultery. (Why should she have so many husbands? Because she is an adulterer.) And it is her story today as the Lord approaches her. She treads the clay path day after day, back and forth, bearing her jar to a man who will not marry her. In this dead-end life, she and the clay have become indistinguishable. The heavy jar dominates her frame now, nearly has become part of her. It is crazed with cracks, and it leaks just as the light of Heaven has been ebbing from her soul for decades.

Then, on a day, she encounters the One Who will free her from her deathlike trance. She will, He says, have no need to come to this well again, for the water He gives will well up within her unto life, a new and purifed inner life. As she stands near to the Holy One of Israel, His radiance, His dunámis, floods into her soul, and she sees a new way. She will become St. Photini, "all light," the first Christian evangelist, and Equal to the Apostles.

Is it unthinkable that a first-century Hebrew woman should become an Apostle, effectively before the Twelve have progressed to these same spiritual heights? It is no less unthinkable that a girl toddler ascending the Temple should supplant it, becoming the living foundation of an abiding Temple and sanctuary effecting human salvation as this pile of heavy, cracked stones cannot. These are the themes with which we continue our forty-day pilgrimage to Bethlehem.

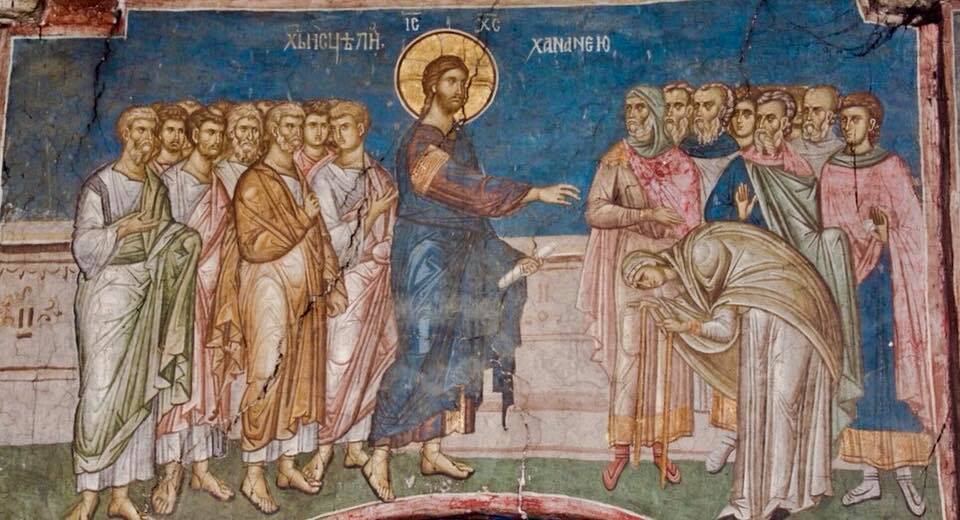

On the Second Sunday, our Gospel lesson presents us with a third daughter of Abraham. She is not the Theotokos. She is not St. Photini. She is more like us. Her life is cut from the same cloth as the Samaritan Woman at the Well or from, say, the demon-possessed Mary of Magdala or like the majority of women (or men) today. She has known demon possession. Jesus discloses that she has been bound by Satan.

What exactly is this bondage? The Greek phrase Luke has written is πνευμα εχουσα / pneuma exousa. The verb form, εχω describes someone who is "unable to resist moral corruption, one who is "unable to attain glorious things." It is impossible for glory to reside within them. Why? Because they are filthy. That is, she has not yet set her gaze on life with God — the normative life established at the Creation for men and women, which is Heavenly glory and salutary thoughts and feelings, which do not yet fill her mind and heart. She has permitted herself to be filled instead with animal desire.

How common is this? To try to substitute God's kind of love with our emotional lusts. How common is this?

Perhaps she has told herself that it is love which fills her heart. But animal desire is not love. Hosea reports that God likens it to a she-donkey with her nostrils to the wind seeking the scent of a man. Love? I think not. By contrast, real love is stable and faithful and pure, animated by a spirit of humility and self-giving. Love has nothing to do with a chronic "giving in to" corrupt thoughts and vile actions.

In this sense, the woman set before us this morning anticipates St. Mary of Egypt, whose life was soaked through with "insatiable and an irrepressible passion," according to her first-hand biographer, St. Zosimas of Palestine. The duration of the Desert Mother's dissipation had been seventeen years. The woman standing before Jesus today in the synagogue has lived this same vile life for eighteen years, nearly identical.

In this, the Holy Spirit presents two "Marys" to us as we have read in the Desert Mother's story. For it would be the light of the Most Holy Theotokos who would guide her path to the Holy Cross and thence to Heaven's gate during another Great Fast of .... not forty days, but forty-seven years. That is, forty plus seven (two significant numbers), as we read in St. Mary of Egypt's biography.

During a period of eighteen years, this daughter of Abraham has trod the path of clay, each year bowing lower and lower to the earthy things she had made her god. And now she is literally bent over, turning back into earth, which she has chosen for her inheritance.

This is not so strange. Is this not the the same process we see all around us? Yes, we see those who are filled with light, who understand their love to be holy and their bodies to be sacred, ascending towards Heaven hand in hand as husbands and wives. And we also see those who have made animal desire their god invariably becoming riddled with diseases, many of them incurable, causing them to begin the process of rotting even before they are dead — a grisly foretaste of the dark kingdom to come. Are these diseases not evidences of Hell's the claim upon humanity, upon living, breathing souls? Are they not a material sign of the spiritual reality whose claims can never be eluded? No, we cannot escape once we head down this path except by parting from this path, by turning our whole life around.

Surely, this woman has turned away from Heaven. Surely, she (among myriad others) is the one to whom the Baptist calls (and Jesus): "Metanoiete! Reverse direction! Return to Eden! For you are bound, not for glory, but for putrefaction and eternal death!"

Withal, the woman in the synagogue has nearly completed her journey to earth. She has become nearly all clay. What began as spiritual idolatry has manifested itself physically, and she bows before the demons whom she invited into her life and who now rule her. She has gone much farther down the clay path than the Woman at the Well. And her pilgrimage to Satan has now become manifest to all.

You see, in Photini's case, Jesus explicates her life for her. And she runs into town making a public confession: "He told me everything ever I did!" Jesus need not explicate today in the synagogue. For the woman's body, like that of Dorian Gray, has become a vivid expression of her diseased, lust-filled interior.

That Jesus evinces His Divinity to the crowd is beyond dispute. He sees her and knows her inner state as the others do not. This detail concerning the eighteen year is uncanny. He knows when her life of sexual depravity began. He knows how it went. And He views now its end. His Divine authority is plain for all to see.

His bearing is that of a king. He does not go over to her in solicitude (as so many preachers depict), but rather He summons her. He does not stand. He is enthroned, if you like, for He was fulfilling His office as teacher. He is in the chair. He announces her release by fiat: "Woman, you are loosed!" His words are not descriptive. They are a Divine speech-act: the speaking of it is the doing of it.

He presents a picture of royal authority, and He is met on the grounds of His authority:

|

But the ruler of the synagogue answered with indignation, because Jesus had healed on the Sabbath;

and he said to the crowd, "There are six days on which men ought to work; therefore come and be healed on them, and not on the Sabbath day." (Lu 13:14) |

In this, he quotes Moses:

|

Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is the Sabbath of the Lord your God.

In it you shall do no work: you, nor your son, nor your daughter, nor your male servant, nor your female servant, nor your cattle, nor your stranger who is within your gates. (Exod 20:10) |

Two opposing authorities speak. One reports the Law received on Mt. Sinai. The Other is Mount Sinai, the living, present words and power of God.

What is the scene for this encounter? Where and how is it set? The place in Greek is called the συναγωγή, / sunagoge defined as "an assembly of Jews formally gathered together to offer prayer and listen to the reading and exposition of Holy Scripture." This definition is mostly right. For as we consider the original establishment of the synagogues, unknown before the Return from Babylon, we understand them to be part of a propaganda program rolled out to socialize the Levant to the invented religion: Judah-ism. In practice, synagogues were closer to being community centers (the literal meaning of the word), where among other functions Scripture was read and debated and local prayers were offered.

By Jesus' time, half-a-millennium following the Return, Jewish synagogues were scattered throughout the Roman Empire. Manifestly, they would not have been strictly controlled by the Second Temple, not in sectarian Judaism, where many patterns of Hebrew belief were expressed as a prism having many facets, belonging to many sons and daughters of Abraham .... and many of them diametrically opposed to one another.

Some synagogue rulers, for example, had become followers of Jesus. As St. John the Theologian reports,

|

Nevertheless even among the rulers many believed in Him, but because of the

Pharisees they did not confess Him, lest they should be put out of the synagogue; (Jn 12:42) |

They didn't want to lose their jobs.

It is this tension which informs our Gospel lesson this morning. Was not the synagogue ruler the one who had invited Jesus to teach there in the first place? Yet now he evidently feels conflicted as Jesus' antagonists are also present. He's caught in the crossfire, you see.

Another synagogue ruler was Nicodemus. Again, St. John reports,

|

There was a man of the Pharisees named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews. This man

came to Jesus by night and said to Him, "Rabbi, we know that You are a teacher come from God; for no one can do these signs that You do unless God is with Him." (Jn 3:1-3) |

Should we read on, we would discover that Nicodemus is hobbled by his literalist reading of the Scripture. He's something of a fundamentalist. "How can man return back to his mother's womb and be born again?" he asks. But, of course, as a synagogue ruler, likely to have been appointed by the literalist Sadducees, he represents a way of seeing and being: the way of Moses, the way of the Law.

The Temple elders taught that there were forty-eight prophets and seven prophetesses of the tradition (later written down in the Babylonian Talmud). The last prophet would have been been Malachi, at which time "Shechinah [the Presence of God] departed from Israel." No more prophets. No more presence of God.

Do you see how the propaganda machine works? According to this teaching, there can be no John the Baptist, whom Jesus reveals to be, mysteriously, the coming of Elijah. There can be no Son of God. The minds and hearts of Judeans must be bound within the iron Law of Moses.

Today's lesson asks a question, therefore. It is high noon at the synagogue on this Saturday. The claims of Moses for God's nature and mind are presented. The ruler, in effect, says, "The only way ahead is to walk the path of the clay tablets! It is written!"

But the reply of God is also heard. Yes, the clay tablets guide us on in our way of life. They prescribe a safe and salutary path ahead. But what of those who did not heed them? Will the clay tablets now transform the Samaritan Woman at the Well into a St. Photini? Will clay tables transform this woman, nearly all clay, back into a creature of light? "You desire your justice to be perfect," Jesus suggests, "but where, at long last, is your hesed, your mercy?"

|

"So ought not this woman, being a daughter of Abraham, whom Satan has bound

— think of it —

for eighteen years, be loosed from this bond on the Sabbath?" And when He said these things, all His adversaries were put to shame; and all the multitude rejoiced for all the glorious things that were done by Him." (Lu 13:16-17) |

We are told, "glorious things were done." Glory is filling the minds and souls of all present. Remember the woman's infirmity: pneuma exousa, a state of being in which one cannot attain glory. But glory is radiating from Heaven through its One Lord. Glory is reflected in a woman whose clay is being revivified, even scattered like dust, by the breath of God. She is reborn right before the eyes of everyone present (which we pray included Nicodemus).

In the place of this gathering of community, where many patterns of Hebrew belief were expressed, two opposing authorities speak. They speak in an epic-scale: of Moses, of Mount Sinai, of God. The moment is electric. The people have gathered. And in their seeking, in their searching faithfulness, on this day, they have seen God.

May we, my brothers and sisters,

who turn back to our pilgrim path today

see Him.

For He is the Lord of Hosts.

He is the King of glory.

And

His desire is that we know Him,

that we follow Him,

and

that we may always be filled with His glory.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.