Luke 24:12-35 (Matins)

Galatians 5:22-6:2

Matthew 11:27-30

"Take My Yoke"

"Take My Yoke Upon You."

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.

Amen.

Already we have come to the midpoint of our Nativity pilgrimage,

to the "high day."

We arrive to the Third Sunday.

On each past Sunday, we have received crucial lessons from the Holy Spirit

revealing the nature of our lives,

even our composition as human beings,

both material and spiritual.

Now,

on the third Sunday revelation awaits.

This is to be expected in any spiritual quest.

Figures like

C. G. Jung, Mercia Eliade, Joseph Campbell,

among others

document that Divine aid is an essential part of the quest:

information is revealed;

tools are given.

Our most cherished Russian Orthodox theologians say that encounter

lies at the heart of our journey into the Divine.

On this Sunday,

transcending the Gospel narrative surrounding it,

we encounter God.

The language is other,

like a dense jewel laid before us on a white cloth.

In the wisdom of our lectionary,

its few words are as compact as a cut diamond:

All things have been delivered to Me by My Father,

and no one knows the Son except the Father.

Nor does anyone know the Father except the Son,

and the one to whom the Son wills to reveal Him.

(Mt 11:27)

|

We remove our sandals!

For surely this lone verse is holy ground.

Suddenly, we stand in the midst of God's Presence:

Revelation.

It is an encounter .... yet not an encounter,

for it is encased in this diamond-like hardness.

Indeed,

the kernel of it is self-enclosed:

The Father alone knows the Son.

The Son alone knows the Father.

|

All else is void.

You see,

all life is inside it,

and

outside it, nothing, until God wills it to be something.

As Jesus has offered these words to us,

however,

we realize we are not to stand by passive,

but

rather called to contemplate and discern.

We dig deeper.

The verb spoken by Jesus is

επιγινώσκω

/

epiginósko

which means "to know,"

yet this is a very special kind of knowledge.

The surface meaning is "to know very well."

But at a deeper level we find the root

γένος

/

génos

which takes our breath away.

For we begin to draw near to a deepest mystery,

an incommensurable,

far beyond our reach.

For this word

communicates

the Son's Only-begotten relationship with the Father.

Génos

invokes awe.

It is a word which tore the Church apart for centuries

and

continues to separate jurisdictions of Holy Orthodoxy.

For the relationship between the Father and the Son

belongs to no human domain of inquiry

nor

could ever be compassed by human reason.

This is knowledge which is not knowledge,

for it it cannot be anatomized according to attributes or properties.

We cannot see, hear, smell, or touch it.

No instrument might detect it.

This

génos

(the root of our modern word gene)

points to the inner reality of God.

As God is Uncreated,

apart from the Created Order,

so His Self-contained Perfection remains aloof.

We cannot say what Only-begotten means .... except,

owing to Jesus' selection of this verb,

we see that it

expresses a kind of coalescence of two things:

a special kind of knowing and an inscrutable world of Uncreated Generative Being.

This morning, Jesus presents us with an equation:

the Son is the Father,

and

the Father is the Son.

They are One (Jn 17:11).

Within this Self-enclosed Sphere resides the Divine.

Scattered all around it is the fragmentary, impoverished, and constantly revised

domain of human knowledge.

During

the first way station

on our road to Bethlehem,

we learned that this

disjunction

goes to the essence of the human creature at our creation.

Our order of knowledge

(epistemē),

Vladimir Lossky writes,

is limited to the material world as its domain.

The order of knowledge associated with God (gnōsis)

we call revelation.

It is granted through encounter:

"the one to whom the Son wills to reveal,"

as we read in our Gospel lesson.

This

revelation

points to an enduring boundary drawn at the Creation across the human reality.

It was the

only boundary drawn in Eden,

for God did not even bound Himself off from human company and discourse.

The enduring boundary is

Divine Knowledge

figured in

the Tree of Knowledge.

In this,

we understand that our human nature participates in a boundary and definition concerning God.

Our own persons are part of this

incommensurable mystery

concerning the Son and the Father,

therefore.

You see,

God's Nature goes to the heart of the human condition

—

the condition made at our creation .... "this you cannot do."

It goes to our DNA,

our nature,

and

our essence or ousia as creatures.

Is this not the cause for Jesus revealing His Only-begotten nature to us?

He reveals the part which is for us

and

the part which is not for us.

Still, He offers.

He speaks to us.

We are to have some part in this,

for we may be

|

.... the one to whom the Son wills to reveal ....

(Mt 11:27)

|

We see that this possible sharing is not structural.

It is not native to us.

It is not ours to claim as a right or prerogative

which we might possess.

Rather,

we are touched by the will of God at a time and place of His choosing.

This is basic to Christian life:

|

"You did not choose Me, but I chose you and appointed you."

(Jn 15:16)

|

☦

At the midpoint of our trek to Bethlehem,

a gift is given.

And the Giver

has prepared us to receive it by inviting us to ponder His Nature,

which is simultaneously Divine and human.

Now, which gift could be more fitting on the eve of His Incarnation?

He and the Father are an inviolable, unknowable Unity

yet at the same time

a Possibility in Which the human creature might participate.

Here we stand on the edge between

epistemē

and

gnōsis,

between human knowledge and Divine Inter-knowing.

The hidden road between these domains Jesus has disclosed this morning:

"the one to whom the Son wills to reveal."

Encounter .... Revelation .... these open like brilliant portals

into the Kingdom at the will of God.

It is here,

at this

superabundant place of all human possibility and hope,

where the real encounter takes place.

For the very next words Jesus will speak are these:

"Come to Me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.

Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart,

and you will find rest for your souls. For My yoke is easy and My burden is light."

(Mt 11:28-30)

|

In an instant,

He had just uttered the dense, jewel-like language pointing to the mystery of His Nature;

in the next, the mud-caked, homely language of the yoke and plow.

How extraordinary!

And this is our entire Gospel lesson today

—

an incommensurable mystery expressed in a single verse,

then

a barnyard scene following it.

Still,

we must not be fooled.

For this yoke

is tied to a Divine command (the imperative verb take)

and

it constitutes a mysterious encounter:

Take my yoke.

What can this mean in practice?

Who has not heard these three words?

Perhaps they have conveyed acceptance to Christians over the many centuries.

The words are personally comforting as few others are in the Gospels.

Remarkably, they

refer to Jesus' inner nature:

"I am gentle and lowly .... You will find rest for your souls."

Where else in the Gospels do you find such language?

I know that we have loved to characterize Jesus with words like these.

We say that He is gentle and lowly, meek, and mild.

But, truly, where else in the Gospels do you find language like this?

But let us go back to the idea of the yoke.

The

yoke's

reason for being

is to join two.

It is an instrument for achieving unity between

two different minds,

two different wills,

two different directions,

even

two different timings or pacings

going to the level of muscle memory.

The yoke does not contemplate three.

Even into the early twentieth century,

horses were paired, never tripled.

The more elaborate configurations in common use

—

say, the "carriage and six"

—

only paired horses two abreast.

I suppose many imagine themselves to be paired to a friend

or

to their spouse

or

to their spiritual father or mother.

It is natural to contemplate such partners,

but Jesus' words do not contemplate this.

Only two are contemplated:

ourselves,

the implied subject of the imperative verb "take"

("you take")

and

the Lord Jesus.

He tells us that this is His yoke.

He is the Other Who will be joined to us.

We are the pair.

What will be our our pacing .... our direction .... our inner reality?

The formation He has planned we call theosis.

A simple statement is made in

the thirteenth-century prayer of Richard of Chichester:

Day by day, three things I pray.

To see Thee more clearly,

follow Thee more nearly,

love Thee more dearly.

|

In this clear and near and dear following,

every day,

up-and-down many fields,

through which we grow, .... we grow to become like Him.

Slowly,

our willful minds quiet.

Our direction becomes His direction.

Our inner timing and pacing and instincts for words and motion and actions

become indistinguishable from His.

You see,

this is not authoritarian rule imposed from without,

which diminishes us.

No,

it comes from within,

from the deepest places inside us we call life.

We are transformed emanating from the place of our own essence,

which He created from the beginning.

He breathed His breath into us.

We are elevated,

freed from our narrow (and often self-destructive) categories.

We rise above the hardening clay of ego-life.

"Oh, my!"

we think.

"What a marvelous instrument is this

which performs wonder-working surgery!"

Yet,

it is made not from fine Sheffield steel.

It is not a surgical laser.

It is a yoke, made of wood.

What precisely can this yoke be then to be so endowed with life-giving properties?

What is this transforming and life-giving instrument of wood?

It is the Holy Cross.

The yoke is the Cross.

It is obvious to every Christian once it is stated.

Yet,

it is a connection that has not been obvious to many Who have professed Christ.

Nonetheless,

this equation,

the yoke and the Cross,

is the kernel of religious life.

It lies at the very place where Christians enter the angelic schema

of monastic vows.

It forms the gateway into "angel life."

In our Church's Great Book of Needs.

the ritual of monastic vows begins with "Take my yoke!"

This commences the vows:

Will you abide in the monastery as long as you shall live?

Will you keep to yourself your virginity (which God restores where it is lost) and chastity?

Will you be obedient to the abbot and the brethren or sisters?

Will you forget about possessions and live the common life of Christ and the Apostles?

Then immediately are

the words of our Lord:

"If any man would come after Me, let him deny himself,

and take up his cross, and follow Me." (Mt 16:24)

(Mt 16:24)

|

Do you see the structure?

The gateway into angel life is framed by the yoke and the Cross.

There are no words following the first

and

no words preceding the second.

Here is another dense jewel:

the door into angel life.

Revealed here are

the life-giving properties of the Holy Cross.

The Cross steadies us and

rights us.

It is, after all,

the Great Compass driven deep into the earth.

It is the Crossroads of the world.

Upon it we see inscribed the cardinal directions,

whose letters in Greek are,

"A," "D," "A," "M."

That is,

a new order of life is revealed,

cleansed,

restored,

and

now made permanent.

Yet we must prepare ourselves to enter this transformation.

For a noble metal cannot be poured into a crucible still containing remnants of old lead or iron ....

no more than the breath of God can be breathed into a mind and soul still clinging to earthly filth.

It is this Cross which strips away the debris of the world.

It is this Cross which straightens our crooked lives so out-of-joint with Heaven's Kingdom.

It is this Cross which supports us and measures us and points the way to our full stature in Christ.

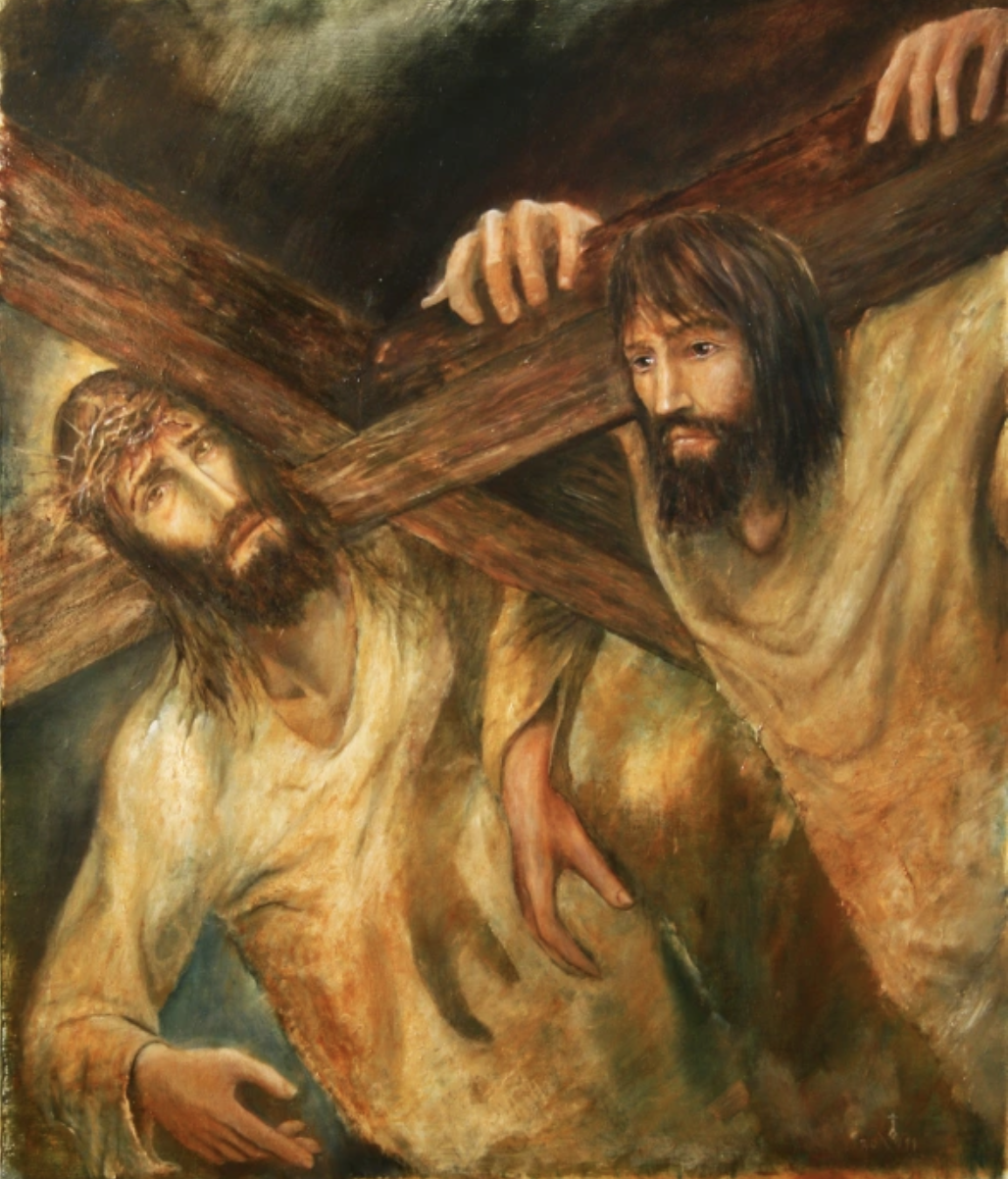

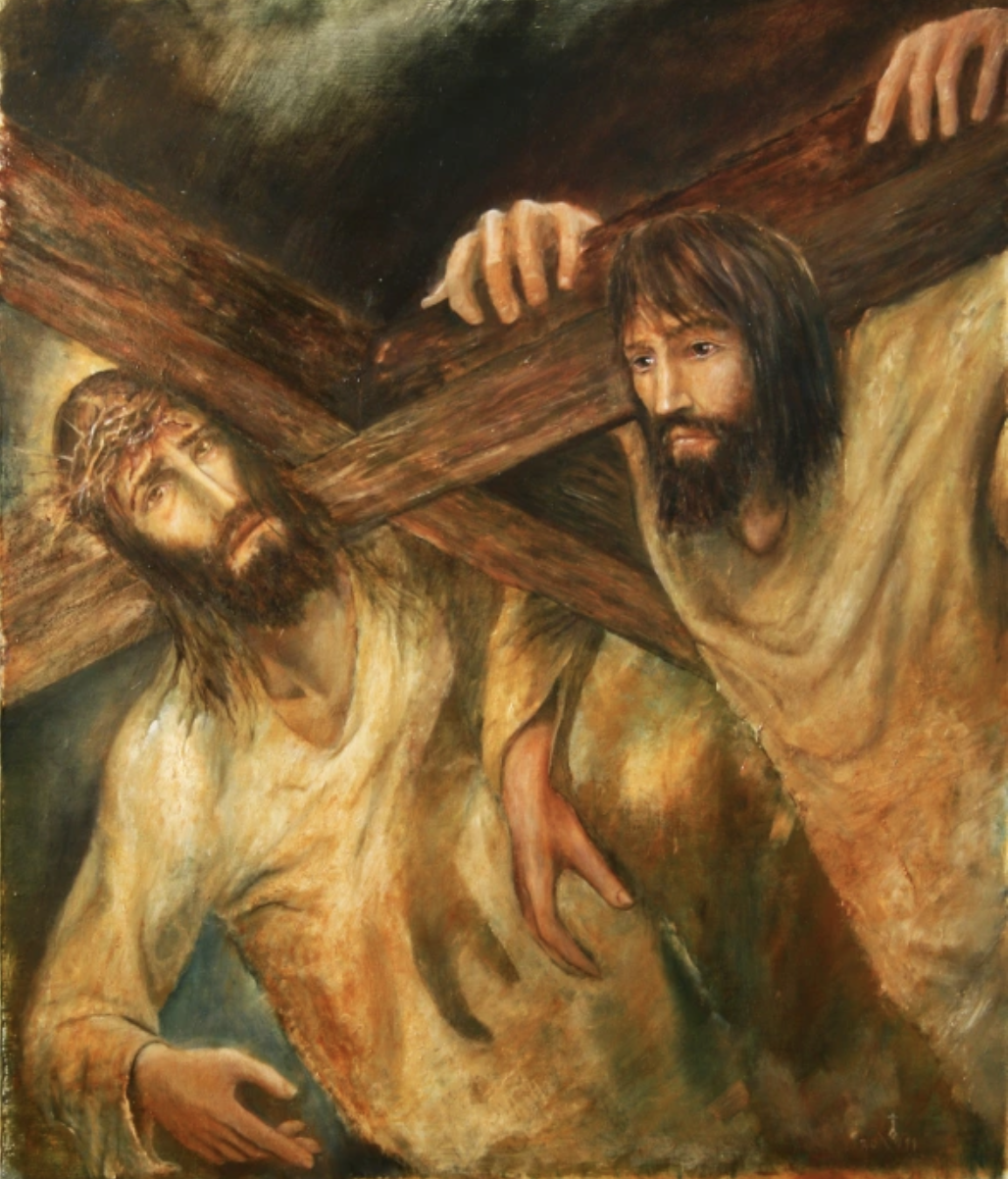

It is this Cross which unites us to Him,

yoked to Him,

as Simon of Cyrene discovered on that fateful Friday.

Are we at the Hermitage suggesting that all Christians ought to enter angel life?

Yes, of course we are!

The call to sanctity is universal.

The yearning for purity and goodness is the holy seed planted

within us at birth.

It is the nucleus of our souls.

And it is our common pilgrim road:

The Way,

the earliest name for Christianity,

which

is the Way of the Cross.

Many will ask,

"But what of our human desires and pleasures?

Have they no place in Heaven?"

We recall the men who asked Jesus about sexual pleasure in Heaven:

"In the Resurrection, whose wife of the seven will she be?

For they all had her."

(Mt 22:27)

|

Jesus replies that such thoughts are alien to Heavenly life and atmosphere.

The atmosphere of the Kingdom is angel life:

"but are like angels of God in Heaven"

(Mt 22:30).

Here on the Third Sunday of the Nativity Fast,

angel life is broached.

Our passage into this impossible lightness of being begins with a yoke,

which Jesus promises will grant us rest to our very souls.

He becomes our Teacher and the prepossessing Force and Power all around us.

We are corrected.

We are formed.

We are guided.

Is this not why we departed on the pilgrimage in the first place?

Surely, this is "yoke life."

In the mysterious goodness of God,

yoke life turns out to be the confinement which frees us.

It is the sweet spot of life

recalling the ancient prayer:

"To know you is life. And to serve you is perfect freedom"

—

the servant-hood which alone will liberate us.

He encounters us.

He commands us, "Take My yoke upon you."

We are placed intimately beside Him in a kind of mutual indwelling.

Mysteriously, we come to know Him (gnōsis).

In this, revelation is completed.

Somehow, we participate in Father-Son Unity .... slowly, seamlessly, without awareness of boundaries,

not through any capacity of our own,

but rather by emptying ourselves of capacity and willfulness.

Emptying ourselves.

The gift we receive today is fitting and right.

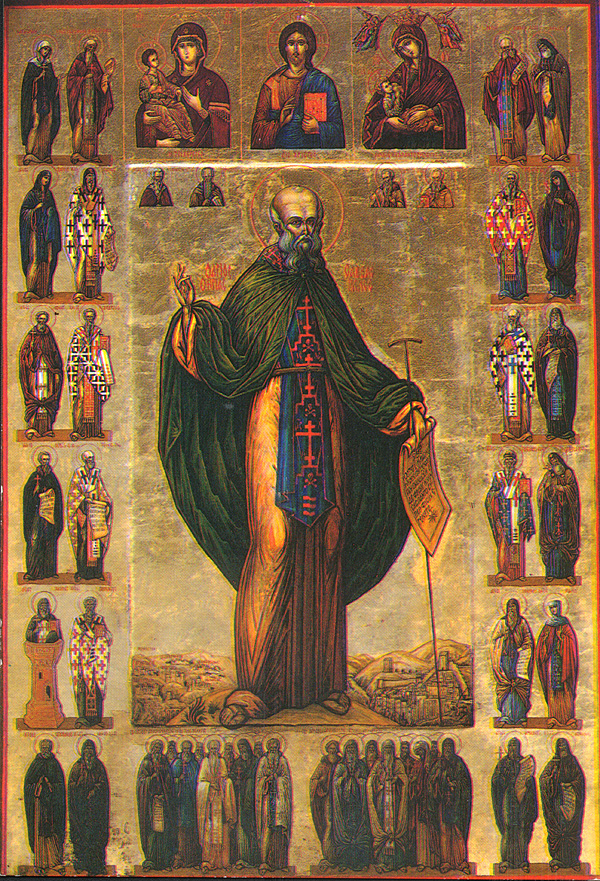

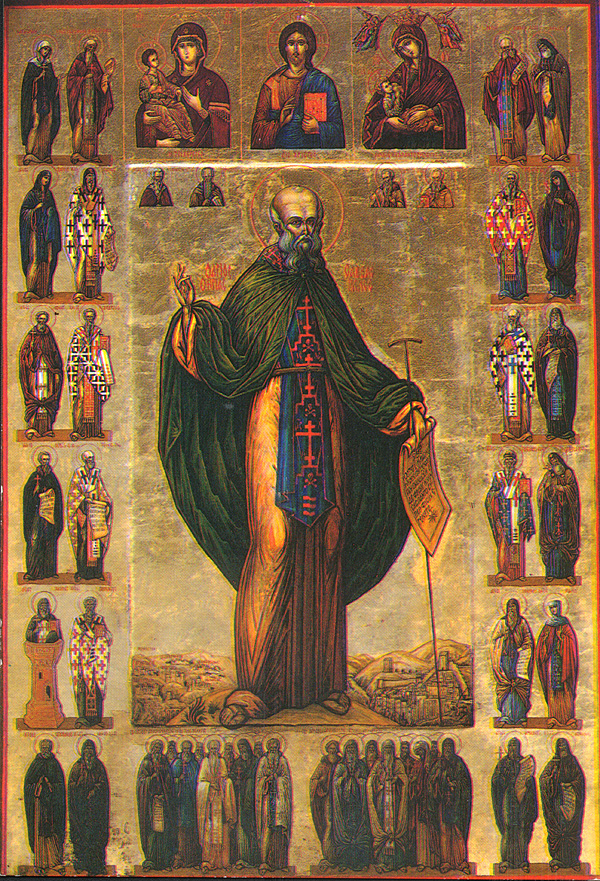

For the Third Sunday of the Nativity Fast is

the Feast of St. Sabbas the Sanctified,

whose name means "the old man who ascended to angel life."

His name expresses the idea of pilgrimage.

His lavras would become a teeming womb of holy men,

writing guide books for countless pilgrims who followed including ourselves.

How did these holy men find their way?

They discovered the golden thread of self-forgetting.

This is the primary path running through all holy life,

running through the lives of St. Anthony of the Desert,

of St. Sabbas,

of St. Isaac of Nineveh after him,

and

down to

St. Paisios today.

It is captured in a poem written by St. Isaac,

who was something of a spiritual father to St. Paisios

(though he lived thirteen centuries later):

Let us take refuge in the Lord.

And ascend a little to the place

Where thoughts dry up

And stirrings vanish,

Where memories fade away,

And the passions die,

Where human nature becomes serene

And is transformed

As it stands in the other world.

(The Second Part. 10.28)

|

Let us take up their guide books.

Let us read their poems.

For these souls were the transparent holy ones who entered

the seamless embrace of unity with God.

Forward, then, O sweet life!

Forward to Bethlehem!

For God is to be born amongst us.

Forward to the place where the universe will be unhinged and then reset,

where the inexorable path towards death is transformed into ascent to God's own Kingdom.

For all who are heavy laden and weary and who seek rest,

all,

have been accepted as His.

Take this yoke,

for the mysterious embrace that awaits us is Life Itself.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.