Many of our Gospel lessons ask us to enter mysteries with a sense of awe. These are authentic encounters with the living God in His manifestation as the Word. Yet others are simple and simply filled with the divine light of innocence inviting us to breathe pure air. It is this second kind we enter today.

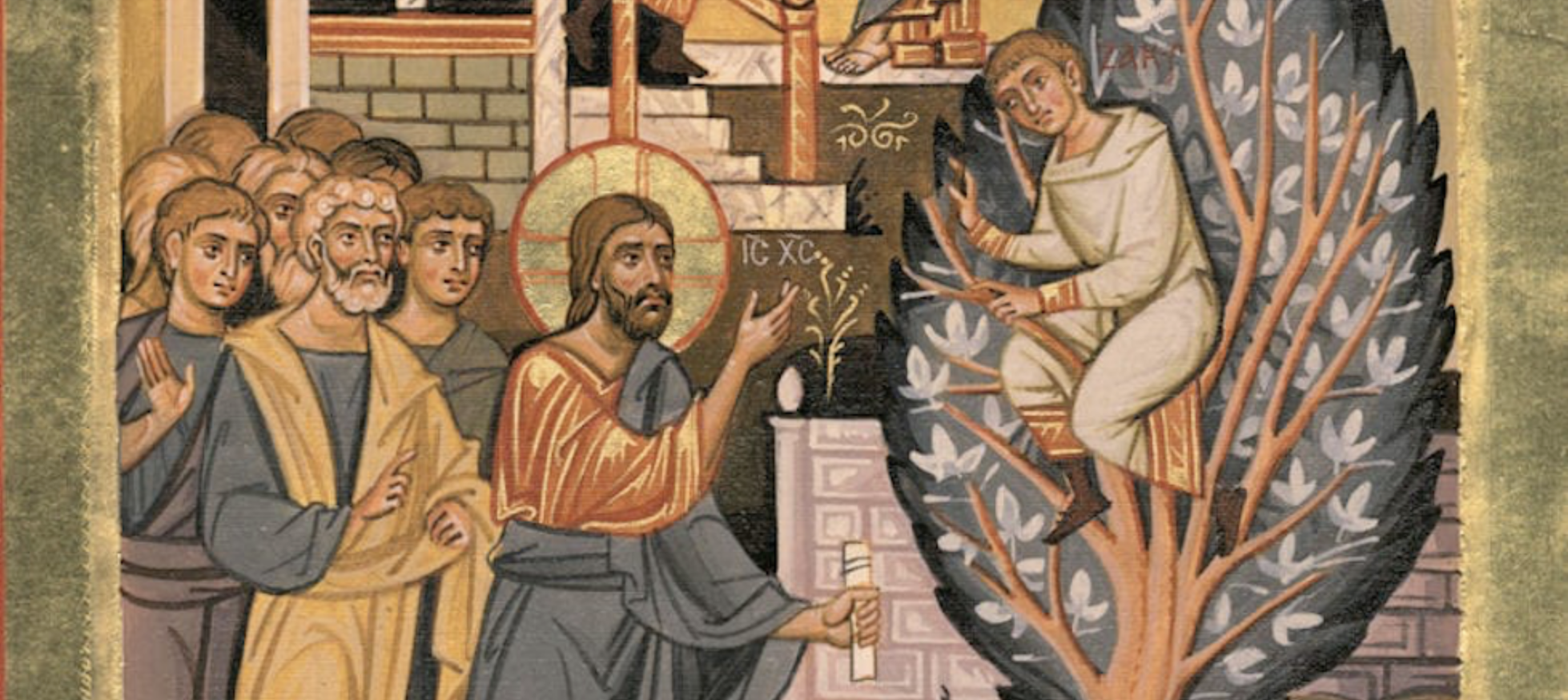

Which Sunday school classroom does not feature a depiction of Zacchaeus? He is always a cartoonish figure, up in a tree, usually appearing as a boy. Perhaps the picture is drawn in crayon by a young student. Without realizing it, these young artists are responding to something just below the surface in St. Luke's narrative.

The name Zacchaeus is not Greek and does not appear in standard lexicons of Classical Greek. It is also not Aramaic, the language spoken along side Greek in Judah. It is from the Hebrew language and means pure, innocent. It was used to denote a young boy, perhaps as a nickname. His element is tree-climbing. His small stature is that of a boy.

Jesus roams the Levant imploring us to be transformed back to our former innocence (Mt 18:3). His Forerunner had preceded him exhorting us to return to purity washing away the polluting effects of experience. This scene along the road depicts this transformation precisely. This grown man who had climbed a tall Sycamore is a psychological reality more than a plausible occurence. It is a sudden departure from the narrative .... not to the absurd, but not to the ordinary and expected either.

The chief tax collector would have been a dignified figure in Roman society. Under the Roman Republic, he would have supervised large projects such as the ambitious harbor at Caesarea Maritima or the great Temple to Augustus Caesar at Banaeus. Or he would have been responsible for supplying Roman Legions in the field with food and other necessary materiel. With the rise of a large bureaucracy during the early Empire, the importance of the Chief Publican began to diminish. But whatever the scope of his responsibilities, he would have been respected .... and respectable, a member of the Societas publicanorum of the Equestrian class, just below the Senatorial class.

Publicans had been notoriously corrupt during the Republic, but the Emperor Augustus had reformed the system, and by the time Zacchaeus was holding office, it was tightly regulated.

He would have been hated by Zealots and other Judean nationalists as collaborating with an occupying force. But these were the outliers of Judean society. Judah had been a vassal state for seven centuries and had accommodated itself to this way of life. Zacchaeus would have been accorded the same respect as other Roman officials. He was a chief tax collector and rich. If he had wanted to see Jesus, he certainly could have arranged a meeting inviting him to a dinner party. Or he could requested an interview. Or like the faithful centurion, he could have approached Him personally at an opportune time. What actually happens is outlandish. We might say Zacchaeus steps out of the background of decorous society into a space that is "other."

With this in mind, let us consider St. Luke as an icon painter. It is characteristic of the icon to diminish the surrounding figures, pushing them aside, while a stylized, main figure commands attention.

Look at our icons. The main subject is rarely what you would expect the historical person to look like. He or she participates in a deeper meaning for which purpose the icon was painted. In St. Luke's Gospel certain figures are seen to step out of the ordinary narrative into a spotlight, so to speak. Consider the example of Mary's visit to her cousin Elizabeth. The lights are dimmed on the background details while the figure of Mary is magnified as she sings the Magnificat (Lu 2:28-32). If this were opera, we would say she performs an aria.

Consider the silent night of Bethlehem with the other figures disappearing into darkness below as the angels perform the Gloria in excelsis Deo (Lu 2:13-14).

Or consider the example of Joseph and Mary presenting the infant Jesus at the Temple. The prophet Simeon steps out of the background and the other figures fall to silence, while he sings his great aria, the Nunc Dimittis (Lu 2:29-32).

Or consider the example of Zachariah, who has been mute for nine months until the time of his son's birth (Lu 1:20). But then he writes on a slate, "His name is John" (Lu 1:63) expressing obedience to God's will, and all else fades to a background as he sings his aria, the Benedictus.

The most imposing example of this technique in St. Luke's art occurs at Pentecost. Now, the founding of the Church in the Gospels occurs in the upper room with perhaps ten Disciples present according to St. John (Jn 20:22) (who is the theological norm for the Orthodox confession of faith). But in St. Luke's version, an other-worldly transformation takes place. It begins in the upper room in a "house where they were sitting" (Acts 2:2). But then this modest stage gives way to a grand spectacle in a public square in Jerusalem and thence to the whole world: Parthia, Media, Elam, Mesopotamia, Judea, Cappadocia, Pontus, Asia, Phrygia, Pamphylia, Egypt, Lybia, Cyrene, Rome, the Jewish Diaspora, Crete, and Arabia. And upon this high stage, with eleven other Apostles standing mute, St. Peter sings an aria of twenty-two verses. The Holy Spirit has descended like a mighty wind. The ordinary is pushed aside. Anything is possible. The Apostles, with the most Holy Mother of God, are depicted in high relief. Here is the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church — universal in scope and self-evidently Divine. This in no ordinary narrative. This is some other artform.

But if Zacchaeus breaks from the decorum of the surrounding society, what does it mean? We might say that no Judean is more worldly than a Publican. He has made his bargain with the Roman Empire, and this must be his identity forever after. He must inhabit a certain dignity. He must choose the ones on whom he smiles. He must maintain a certain aloofness.

Yet, through the vagaries of life as an imperial official, Zacchaeus seems to have hung on, in some measure, to his original innocence and purity. Yes, he played the game of the Roman official and played it at a very high level. But through it all, he never lost sight of his soul, and his soul somehow has retained its childlike glow.

In the presence of God, he now throws off the distinguished robes of office, so to speak, and appears in a garment he knows God will not despise — the ebullient, innocent heart of a boy.

The scene is not to the extreme of, say, the Apostles appearing skinny-dipping at the waterhole calling each other Petey, Johnny, Tommy, and Jimmy — but the name Zacchaeus is precisely that, and it is of a piece with tree-climbing.

After all, as we pass from innocence to experience, as every one must, what exactly is this rite of passage? What is this adult world we are passing into? We use the word adulterate to mean contaminate, to pollute the pure with the impure. Certainly, the signature sin of adulthood is impure sexuality, unknown to the child. It is for this reason that I deem all sexual sin as being adultery. All who have ventured into sex outside of marriage have broken God's prohibition of adultery.

What would an icon of Metanoia look like? After all, here is the very heart of Christianity: the transformation from experience back into purity. Jesus says, "Today salvation has come to this house" (Lu 19:9). Salvation, σωτερία / sotería — this word might mean a number of things including safety or protection. But the definition that makes most sense to me is safe return in the sense of a rescue. God cannot save us. If this were true, He would not have sent His forerunner crying in the wilderness "Metanoeite," and He would not have made this word the hallmark of His own reign on the earth. Sotería must come from within. We must effect this rescue. There is no other remedy.

From what must we be rescued? St. John says it is the world with its inevitable entanglements of carnality and materialism, the two driving wheels of the human breast in adulthood, which is our poison. We call this experience. The rescue must proceed first from the heart, and then it must be guarded by the will. We must stay the course to the end. We must break the poisonous chains and entanglements of experience, returning to the mind and heart of our childhood, which we remember.

Is this my pondering or meditation? No. It is Jesus who proposes this:

|

At that time the disciples came to Jesus, saying,

"Who then is greatest in the Kingdom of Heaven?" Then Jesus called a little child to Him, set him in the midst of them, and said, "Assuredly, I say to you, unless you are converted and become as little children, you will by no means enter the Kingdom of Heaven. Therefore whoever humbles himself as this little child is the greatest in the Kingdom of Heaven. Whoever receives one little child like this in My name receives Me." (Mt 18:1-5) |

We might ask, "What is the heart of Jesus?" It is the heart of innocence. O Lamb of God, O Pure one.

What would an icon of sotería look like? St. Luke, the seasoned writer of icons, who wrote the first icons of the Mother of God, believes that it should depict an interior reality. It should be bold, declaring a rejection of the world. And, certainly, it should clearly announce a "safe return" from the toxic atmosphere of adulthood.

Let us nominate a scene depicted in the public square: a man covered in the world's glory throwing off his dignity, reclaiming his boyhood name, and in the witness of all present, climbing a towering Sycamore, safe from the world below. Is not Zacchaeus half-way to Heaven? Certainly, as a boy when I climbed a tall tree I felt that I was half-way to Heaven.

Vivid!

Memorable!

Touching!

.... and apt to command the attention of everyone who sees it,

an icon painted by the Evangelist who founded the artform

and

brought it to a state of perfection

painted even with Gospel narrative.

How textured!

How deeply dimensional!

Truly, this art breaks through from our gritty world to the good, the true, and the beautiful,

as

otherworldly as the impossible fullness of an aria springing forth from

the narrow confines of the human frame.

Here is the Kingdom of God.

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.