For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that though He was rich, yet

for your sakes He became poor, that you through His poverty might become rich.

(2 Cor 8:9)

The Passion of the Christ, thus, goes to the heart of our part

in the Kingdom of Heaven:

He became poor that we might be made rich.

This idea is further explored in St. Paul's Epistle to the

Philippians:

Let this mind be in you which was also in Christ Jesus, Who, being in the form of God,

did not consider it robbery to be equal with God, but made Himself of no reputation,

taking the form of a bondservant, and coming in the likeness of men. And being found

in appearance as a man, He humbled Himself and became obedient to the point of death,

even the death of the cross.

(Phil 2:5-8)

|

This passage has become the locus classicus

of an important theological idea:

kenósis,

or

"self-emptying."

Christ emptied Himself of His Divinity that we might be filled.

As I said,

He remained fully God,

yet He emptied Himself

suffering death on a Cross.

But key questions remain concerning His Passion.

When did it occur?

In what did it consist?

The answers are not obvious,

and

Hollywood movies will not help.

Was He a Lamb offered in sacrifice?

The Gospels do not say so.

Moreover, St. John the Theologian,

our highest authority,

would have strongly opposed such a view.

St. Athanasius writes that Jesus' Passion began at His Incarnation,

even at His Conception.

Indeed,

it is this Passion, which has saved us.

He emptied Himself of His Divinity in order to take human form.

The cosmic force that was unleashed at the Creator touching the Creation

shocked the world to its very foundations,

flipping its telos from death to life.

For He is Life,

and

death has no victory in His Presence.

The ancient curse of Eden was annulled.

St. Irenaeus wrote that the Christ was to finish the work left undone in Eden.

He would be a second Adam.

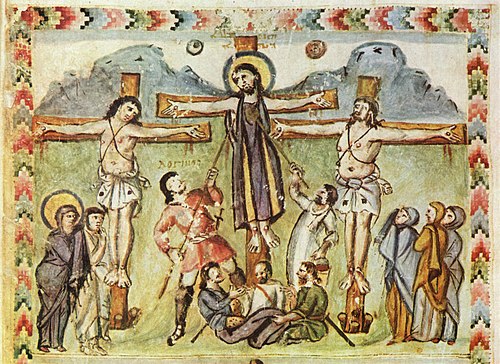

And this would be announced on the Cross,

the Great Compass that pointed in all directions,

whose cardinal points (in Greek) spell

"A", "D", "A", "M",

pointing not ahead to His earthly grave

but

eternally to His Incarnation.

It is the Life of Christ which saves us,

not His death.

The Fathers wrote

that the portrait of humanity had been defaced,

but no one was worthy to sit for it that it might be restored.

The silver coins bearing the Great Emperor's Image had been worn down to dull slugs,

which no one could decipher.

It would be Jesus' lively Image that enabled the painting to be restored

and

the coins

re-stamped.

Is it possible that no one perceived this most momentous event in history?

The greatest spectacle imaginable was performed by God in our midst,

and

no one noticed?!

Well, not no one.

Three wise men from the East could read it in the created order,

and following a star,

they set out to do obeissance a thousand miles from Persia

(evidently starting out around the time of Christ's Conception

to be present for His birth).

Oh yes,

and there were others, possessing a certain wisdom and knowledge of Divine things:

the fallen angels.

For all of His life,

they too did obeissance before Him:

|

And the unclean spirits, whenever they saw Him, fell down before Him and cried out,

saying, "You are the Son of God."

(Mk 3:11)

|

Along the way,

others are granted brief glimpses of His true Identity.

His healings amazed those who beheld them,

but He admonished them that they should not reveal what they had seen.

His Disciples surely must have known.

They ask rhetorically,

"Who then is this Who commands the winds and the seas, and they obey?"

They have seen Him raise the dead .... three times,

and one man after he had been begun to decompose.

("His sister said, 'Lord, by this time he stinketh'" (Jn 11:39)).

They had seen feed multitudes in the wilderness with a kind of manna ....

not once by twice.

And, at moments, they are moved to say, "You are the Son of God."

But, again, He strictly forbade them to reveal it:

|

Then He commanded His disciples that they should tell no one that He was Jesus the Christ.

(Mt 16:20)

|

After all,

could there be even a shadow of a doubt concerning His Divine Identity?

But He dids them remain silent.

But it turns out that perception

is a leading mark on our inner transformation.

And transformation

is the essential purpose of His ministry to us.

He says repeatedly,

|

"They have eyes but they do not see and ears but they do not hear."

|

As we read in our Gospel lesson last Sunday,

"For nothing is secret that will not be revealed,

nor anything hidden that will not be known and come to light"

(Lu 8:16-17)

|

Seeing and hearing as the Son of God sees and hears

—

that is thing:

to know God as He knows us.

This is what we are striving for.

This is the gnosis,

the intimate relationship with God,

which is everything.

This is the measure of theosis.

Victor Lossky writes that this

relationship is

|

participatory adherence to the presence of Him who reveals Himself

(Orthodox Theology, 16).

|

By this, Lossky declares, God is present.

We must attune ourselves to this Presence and account it to be the only reality.

We must calibrate ourselves for the life ahead.

These are the first and the last steps in our journey of theosis.

Until we account God to be the only reality, ultimately,

we are not in it.

We have not yet begun.

Jesus warns

"take heed how you hear" (Lu 8:18)

and

then He adds

"For whoever has to him more will be given; and whoever does not have,

even what he seems to have will be taken from him."

(Lu 8:18)

|

In our present perspective, this makes perfect sense.

I have been present for sermons on this passage

and

hear the priest say,

"What in the world can this mean?!"

But now we understand.

For if we understand the Lord to be the only reality finally,

and

we do hear Him speaking to us,

we will understand more and more and more.

But the one who thinks he understands but grasps nothing,

all he has (which is nothing finally) will be taken away .... unto perdition.

You see we are not in it ....

if we do understand the devil to be everywhere present,

if we do not perceive ourselves to be in the midst of spiritual warfare,

if we do not believe our guardian angel to be ever present,

and

that everything is about God.

In sum,

there are two ways of perceiving, worldly and Heavenly.

In one focus we see that the quotidian world of everyday life.

In the other,

we see the Heavenly ordering of things.

Two ways of perceiving and two ways of being

—

and He reminds His listeners that they cannot maintain both

(which is so common among so-called Christians):

"No one can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other,

or else he will be loyal to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon."

(Mt 6:24)

|

And a tableau of right seeing and hearing is set before us:

And she had a sister called Mary, who also sat at Jesus' feet and heard His word.

But Martha was distracted .... "worried and troubled about many things." But one thing

is needed, [says Jesus] and Mary has chosen that good part, which will not be taken away from her."

(Lu 10:39-41)

|

.... an oblique reference to the passage we just read:

"all that you seem to have will be taken from you"

(you who are preoccupied with worldly things).

Here is the whole program of our conversion.

At His Incarnation,

He had already cleared the way.

From that moment, death had no claim on us.

But our part is that we must accept the gift.

He speaks to us.

And we must reply.

I have shared with you my own horrible .... I mean blessed, experience.

He spoke to me, not once but many times.

I knew very well that He was speaking to me.

But I found ways to put Him off.

Then, He took me by the scruff of my neck and pulled me out of my whole lifeworld

for three years.

Blessed is the man who falls into the hands of the Living God.

We must have the mind of Christ.

Did we not already see the Resurrection in the raising of Lazarus,

in the raising of the widow's only son,

and

in awakening of Jairus' daughter?

Now what shall we say of the Cross?

His Passion began with His self-emptying at His Conception.

At every Liturgy,

we whisper the prayer,

"May be have a share of the Divinity

Who entered the horrible confines of the our narrow humanity?"

For thirty-three years He was confined to a tiny box,

as it were

—

a stifling, suffocating imprisonment.

We cannot imagine the extremes of such horror.

Which would you rather endure:

one afternoon of torture and humiliation

or

thirty-three years of strangling, deforming confinement?

And there are moments when He cries out:

Then Jesus answered and said, "O faithless and perverse generation,

how long shall I be with you? How long shall I bear with you?

(Lu 17:17)

|

I say,

two ways of thinking and being.

How often

do we reflect on Jesus' self-emptying?

I know there are men in Philippines who insist on being nailed to a cross.

How often do we think of Jesus' extreme privations?

Do our hearts quake?

Are tears extorted from our eyes?

Do we ever really meditate on

His setting aside His empyreal glory

and

His stooping down to our mean and gritty world.

All this

is forever enshrined in the Holy Cross,

which all might see and hear,

which might move all to tears.

His Passion

begins at His birth as an outcast

mongst dung-stained hay,

lying in a animal's feeding trough,

and

it ends in that most ignominious death,

reserved for the dregs of society:

death on a Cross.

You see, it all is of a piece.

All is distilled upon that Cross.

Truly,

here is worldly seeing and hearing.

If you did not see the star,

if you did not see His Divinity on full display all of His life,

if you could not make out the Lord of Life midst the everyday and the nothing-special,

if you did not see the Son of God,

then here is a spectacle no one will miss:

the Crucifixion of God.

For He taught His disciples and said to them, "The Son of Man is being betrayed into the

hands of men, and they will kill Him. And after He is killed, He will rise the third day."

(Mk 9:31)

|

Outright. Spoken plainly.

.... and after forty days

Ascended into Heaven,

where multitudes were gathered.

Two ways of seeing:

Heavenly and worldly.

The Cross would provide

an eyeful for those whose

eyes are everywhere .... except upon God.

Isn't that the way of the world?

Her eyes are everywhere.

His eyes are everywhere .... except upon God.

Was the Resurrection to eternal life granted on that day?

No, that had been granted more than three decades earlier.

Was the curse of Eden annulled on that day?

No, that too had already taken place.

Was death conquered on that day?

No, He was never not victor over death.

The drama of the Cross and Resurrection and His Ascension into Heaven

was

to make manifest to all

the Life-giving gifts of God.

As the Risen Christ

(Whom everyone sees)

would say:

|

"Thomas, because you have seen Me, you have believed. Blessed are those

who have not seen and yet have believed."

(Jn 20:29)

|

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.

|