John 20:11-18 (Matins)

Hebrews 11:24-26, 11:32-12:2

John 1:43-51

To the Sources

"Can anything

good come out of Nazareth?" (Jn 1:46)

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

|

In

2019

and

2020

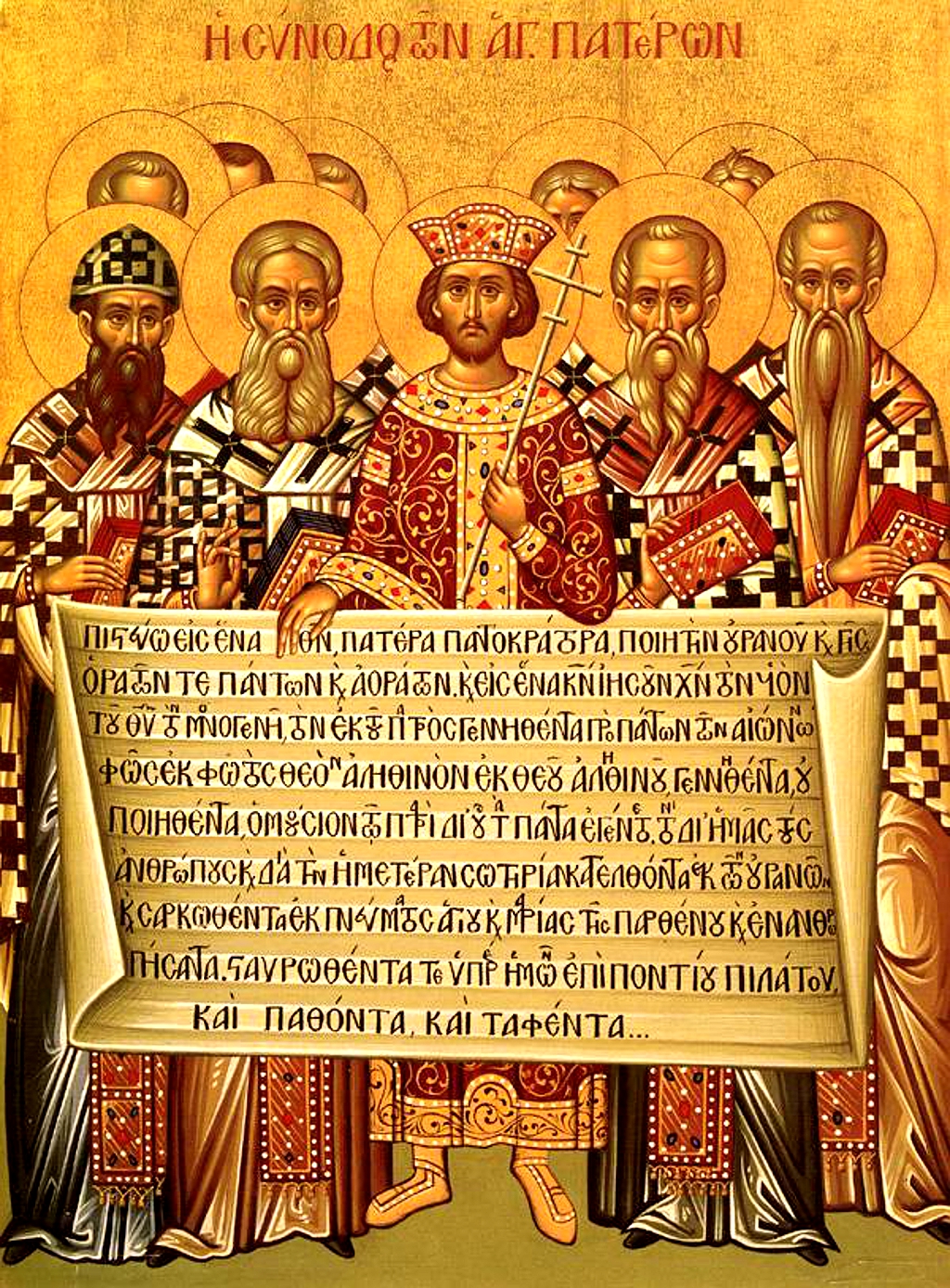

the Hermitage set aside this Sunday to reflect on

the Triumph of Orthodoxy over those who would destroy icons

or

suppress the religious liberty to venerate them.

Today,

on our third observance of this feast as Orthodox Christians,

let us celebrate the Triumph of Orthodoxy in a broader sense.

Let us give thanks for the Christian faith

that has been vouchsafed for us

—

preserved,

guarded,

protected,

and

delivered without blemish following two thousand years of constant assaults,

not only from without,

but also from within.

Chief among these assaults has been a counter-gospel we will call "Progress."

The East and the West.

So different.

In the West, we say that the East is mysterious, spiritual;

its beauty speaks to the soul.

Certainly,

this was the case during the early centuries of the Roman Empire.

The Eastern capital Byzantium bespoke all these things.

Thinking back on this time, the twentieth-century poet W.B. Yeats wrote,

"Therefore I have sailed the seas and come / To the holy city of Byzantium."

to see

".... sages standing in God's holy fire / As in the gold mosaic of a wall."

Meantime,

the Empire's Western capital,

Rome,

was the world's foremost center

for

military science, engineering, and imperial governance

perfected over many generations,

a vast and deep culture formed and trained in the sciences of practicalities.

During the first five centuries of the Church's history,

these differences became glaring and obvious.

In the East,

writing in Greek,

were

Ss Ignatius, Polycarp, Papias, Justin, Irenaeus, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen,

to be followed later by Athanasius, Basil, two Gregories, John Chrysostom, and many more.

Together with the Master and His Apostles,

these are the Holy Fathers who gave us what we know to be Christianity.

The greatest,

and arguably the most influential,

among the Latin Fathers

is St. Augustine,

author of the masterpiece De doctrina Christiana

among other profound writings.

Unfortunately,

this brilliant man

could neither read nor write Greek

isolating himself from the broader consensus of the Church.

Moreover,

the Latin language,

while sharing the active and passive voices of Greek,

lacks its middle voice expressing spiritual subtlety.

Reflecting apart from the Patristic Consensus

and

writing during the fifth century,

Augustine would go in his own direction

—

most notably, inventing the doctrine of Original Sin,

positing man's essential and inescapable depravity.

Accordingly,

the West was forced to develop a special doctrine,

the Immaculate Conception of Mary,

in order to explain

how Jesus' own conception was not spotted with sin.

But this great principle, the East had never lacked.

For the Church has always held

that,

while all humans must enter a fallen world,

each of us is born to be pure.

Do we really need special structures of theology to know that grave sin is noxious to us?

Who is not sick to his stomach upon first being introduced to it?

St. Augustine

lionized the city he termed "the Apostolic See,"

the Patriarchate of Rome,

which was the only one he knew in concrete terms

becoming

an apologist for a nefarious principle:

the primacy of the Roman Pontiff over all jurisdictions of the Church.

In terms of engineering,

the West's material greatness would be built upon a Roman edifice.

Following the fall of Rome, many centuries would pass before

a dome like the Pantheon's could be built again.

And only in the past four years has modern science unlocked the secret

of Roman concrete's longevity (Nature, July 3, 2017).

As for military science and governance,

the Roman Empire continues to inspire awe as a one-of-a-kind,

never to be repeated.

The sciences of practicalities,

which we today call technology,

continue to be the special genius of the West.

Think of the eyes

all over the Eastern and Southern Hemispheres

that first saw a steam engine, an motor car, or an aeroplane.

To these people,

a new and marvelous lifeworld was being displayed.

Surely,

these Westerners must be commanders of the impossible!

This East-West opposition

between material practicalities and spiritual depth

continued for centuries

until the Church herself could no longer contain it.

After one thousand years of unity,

the West's solitary Patriarchate broke off to form its own Church:

the Roman Catholic Church in 1054.

No longer restrained by the other Four Patriarchates,

the Roman Church became fastened upon a more mechanical,

quid-pro-quo theory of atonement:

blood sacrifice in exchange for redemption,

deprecating the more subtle and mysterious

theology of inner transformation.

Where does one hear of theosis in the Roman Catholic Church

though

it constitutes the whole and end of Christian life

and

the primary reason for the Incarnation?

At the heart of the Patristic Consensus lies a great principle:

The Advent of the Lord Jesus Christ was to remind us of who we were

—

children of God

—

and where we were going

—

to Heaven's Kingdom,

a birthright set within us in the form of an immortal soul

and

upon us in the form of God's Image

at birth.

At the same time,

Western theologians introduced a powerful intellectual technology:

a finely reasoned hyperlogic called Scholasticism.

Within a few decades,

a Roman Catholic priest, James of Venice,

was completing a Latin translation (1125-1150) of the Posterior Analytics of Aristotle

propelling Western theology further and further toward rationalism,

leaving far behind her spiritual roots.

They would call this driving engine

the New Logic.

In due time,

this technology would produce systems within systems of intricately reasoned logic

through the intellect of a Dominican monk Thomas Aquinas.

In the West we are apt to congratulate ourselves for being

at the forefront of progress.

We are apt to depreciate the old or the ancient.

My high-school-age Sunday school students a quarter century ago

asked me why anyone would bother to read a two-thousand-year-old, old book from the Middle East.

To them the Bible was incongruous with everything they knew.

They saw themselves

standing on a high mountain with

their fists raised in triumph grasping

their Motorola Star-tac flip-phones

with

all previous centuries bowing before them.

"Burn down the past!"

they implied,

"for today we are the best at everything!"

Perhaps we have all been formed in this

politics of Progress.

I asked my students if we should also throw all literature on the bonfire

—

Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth

—

because

now we have Maya Angelou.

Or should we burn Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven

because now we have the Back Street Boys, the Spice Girls, and Madonna?

Life is not so simple.

Usually a civilization can manage to do a few things very well.

Yes, we have excelled in technology and the hard sciences.

From a spiritual point of view,

however,

our culture,

indeed,

the whole modern era,

stands out as a spiritual

wasteland,

an embarrassment

and

a shame

for the ages.

Christianity in the West

is mostly a history of decline.

The further out we have gone over the millennia from the Advent of God

—

that golden moment when the Son of God dwelt among us

and

taught us

—

the greater has been this falling away.

Meantime,

the Church in the East took measures to minimize these infidelities.

While the Apostles were yet living,

the Church suppressed false teaching

and

censured false teachers.

We see this crisis expressed

repeatedly in the letters of Ss Paul, John, and Peter.

For the first thousand years,

the Church succeeded very well through a strategy of consensus.

The Apostles formed a consensus.

The Fathers of the Church,

and their disciples,

sought consensus

—

both with the Apostolic teachings and with each other.

Today,

the Orthodox Church poses the same question to every theological offering:

"Is it an authentic development of the Apostolic and Patristic Consensus?"

By contrast, the history of the Western Church,

so advanced in engineering and imperial governance,

has left behind a legacy of empire:

of proliferating canon laws

and

the prepossessing intellectual dominance of the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas,

holding the Roman Catholic Church thrall into the twentieth century.

On other imperial fronts,

the Roman Church has anointed herself "empress" over the Five Patriarchates.

This self-promotion reached an audacious zenith with her self-coronation

as the "Catholic Church,"

as if she alone were the ancient Church

founded by Jesus.

In historical fact,

the Roman Catholic Church, founded 1054,

continues in a state of separation from the universal Church by its own hand through a papal bull of

excommunication.

We have seen displays of Roman imperial pomp and majesty

in living memory.

Indeed,

the Roman Pontiff has been the only bishop in the history of the Church of Christ

to

gather around him a secular empire

called the Papal States.

A vestige of this empire continues to be seen in the Vatican,

a glittering display of worldly glory,

over which the pope sits as head of state.

By contrast, the history of the Western Church,

so advanced in engineering and imperial governance,

has left behind a legacy of empire:

of proliferating canon laws

and

the prepossessing intellectual dominance of the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas,

holding the Roman Catholic Church thrall into the twentieth century.

On other imperial fronts,

the Roman Church has anointed herself "empress" over the Five Patriarchates.

This self-promotion reached an audacious zenith with her self-coronation

as the "Catholic Church,"

as if she alone were the ancient Church

founded by Jesus.

In historical fact,

the Roman Catholic Church, founded 1054,

continues in a state of separation from the universal Church by its own hand through a papal bull of

excommunication.

We have seen displays of Roman imperial pomp and majesty

in living memory.

Indeed,

the Roman Pontiff has been the only bishop in the history of the Church of Christ

to

gather around him a secular empire

called the Papal States.

A vestige of this empire continues to be seen in the Vatican,

a glittering display of worldly glory,

over which the pope sits as head of state.

Cutting herself off from the universal Church and her all-important consensus,

the Western Church

produced a system dominated by intellect so different from the Christianity of the early centuries

that

its spiritual dimension had been all but lost.

Scholarship had supplanted participation in the Divine.

The trend continued into the sixteenth century with

an enormous segment of Roman Catholics

—

clergy,

religious,

and

faithful

—

pushing further toward a rationalist church.

They would establish the largest series of dissenting institutions

Christianity had every seen,

all devoted to the "right brain"

and

all rejecting Christian mystery,

except baptism

with Eucharist being demoted to a "love feast."

Their posture of protest would be enshrined in their name:

Protestantism.

The high point of their worship would be a scholarly reading of the Bible

delivered by a man wearing a black, academic robe .... preferably with three stripes on the sleeve.

By the twentieth century,

Roman Catholic figures like Padre Pio were persecuted and discredited

by the Roman hierarchy for no other reason

than that authentic and sacred mysteries,

the Stigmata, were etched upon his person.

And this embarrassed them.

During this same period,

young, brilliant Roman Catholic theologians,

among the greatest of the twentieth century

—

Henri de Lubac, SJ;

Hans Urs von Balthasar, SJ;

and

Joseph Ratzinger,

—

surveyed the scene with horror.

Theologically speaking,

the Western Church had declined into a cult of rationalist philosophy

and

moral

ledger-balancing.

Spiritually speaking,

the faithful

had been handed

a cult of rule-keeping and a "Catholic Answers" mentality

(when the human soul in all places and at all time cries out for spiritual nourishment).

The only solution, these young theologians recognized, must be a return to Orthodoxy.

But how could one achieve so stupendous a feat?

The answer must surely lie in an equally stupendous action:

the convoking of a General Council.

In his own way,

de Lubac,

(later to be styled a "Father of Vatican II")

began teaching a new Catholic faith to the West.

He published a landmark book entitled Catholicisme (Catholicism) in 1938

implying that its pages would define the Catholic faith.

Casual readers in the 1930s might have expected a survey of metaphysics

based on Thomistic philosophy.

Instead,

what they discovered would be an anthology of the Greek Fathers.

Meantime,

other influential voices

began putting out like-minded battle cries:

"Ad fontes" ("Let us return to the pure springs!")

and

Ressourcement ("Let us embrace to the sources of our faith!")

Eventually,

it was hoped,

a General Council might break the iron-fast captivity of philosophical intellectuals

over the soul of the Roman Church.

We today continue to fall into the trap which C.S. Lewis and Owen Barfield called

"chronological snobbery"

—

the defect of mind that automatically looks to the future for what is best

and

discounts everything in the past as being obsolete.

In a materialist setting,

this cast of mind makes sense

as each new scientific discovery discredits its predecessor.

But concerning the great and eternal truths upon which our lives depend?

These cannot be found by peering into the future.

The future is in the opposite direction from our goal.

We must seek God,

and

God revealed Himself once and for all two thousand years ago.

Jesus Christ alone is "the Way, the Truth, and the Life."

And we are enjoined to venerate, reverence, and worship the

sentence that follows this phrase in St. John's Gospel:

|

"No one comes to the Father except through Me."

(Jn 14:6)

|

Except through Me.

This is all that matters where truth is concerned:

final, stable, and eternal truth.

The further we distance ourselves from Him

—

whether it be

through

Aristotle,

marvelous machines,

or

the wizardry of smart phones

—

the more we deepen a great divorce

between ourselves and God,

which equates to eternal death.

Our God is not of the material world,

the world of atoms, cells, and molecules.

Science, much less technology, will never find Him.

On this great feast day,

we give thanks for the most high authority

of the Holy Scriptures.

(As the Fathers have said,

if we perceive a flaw in them,

then we have misread them.

Most likely we have failed to give the spiritual,

which is their primary meaning,

precedence over the literal.)

We give thanks for the Apostolic and Patristic Consensus.

We give thanks for the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church,

who has accepted her vocation as protector of the faith

and

guardian of the Divine truths.

Speaking selfishly

on this Sunday when we celebrate the Triumph of Orthodoxy,

we give thanks to God Almighty that we have been accepted

into the Church

—

we who have wandered so long amidst

heresies,

perversions,

rebellious clergy and religious,

and

had nowhere to lay our heads.

And

we are most grateful

that everyone everywhere continues to be welcomed into the eternal safety of her bosom.

Let us celebrate the Triumph of Orthodoxy.

The Scriptures have been protected and preserved for us.

Theology has been guarded and vouchsafed for future generations.

Our spiritual life and worship spaces have been secured.

The Gate of Heaven has been rightly reverenced and worshiped

and

opened,

therefore,

to us.

All of this,

the most precious of treasures,

has been defended and carried safely

through fierce storms,

through the streets of burning cities,

through war-torn landscapes and prison-camps,

and,

most

impressively,

through a materialist culture of arrogance and skepticism

and the outsized egos of powerful men

.... and the great herd of powerless men fearing ridicule.

Let us give thanks for Orthodoxy

and

for the holy men and women who proceeded us

—

in many, many cases giving their lives for the purity and fidelity of our Christian faith.

Blessed are you, O faithful men and women, for yours in the Kingdom of Heaven!

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost.

By contrast, the history of the Western Church,

so advanced in engineering and imperial governance,

has left behind a legacy of empire:

of proliferating canon laws

and

the prepossessing intellectual dominance of the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas,

holding the Roman Catholic Church thrall into the twentieth century.

On other imperial fronts,

the Roman Church has anointed herself "empress" over the Five Patriarchates.

This self-promotion reached an audacious zenith with her self-coronation

as the "Catholic Church,"

as if she alone were the ancient Church

founded by Jesus.

In historical fact,

the Roman Catholic Church, founded 1054,

continues in a state of separation from the universal Church by its own hand through a papal bull of

excommunication.

We have seen displays of Roman imperial pomp and majesty

in living memory.

Indeed,

the Roman Pontiff has been the only bishop in the history of the Church of Christ

to

gather around him a secular empire

called the Papal States.

A vestige of this empire continues to be seen in the Vatican,

a glittering display of worldly glory,

over which the pope sits as head of state.

By contrast, the history of the Western Church,

so advanced in engineering and imperial governance,

has left behind a legacy of empire:

of proliferating canon laws

and

the prepossessing intellectual dominance of the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas,

holding the Roman Catholic Church thrall into the twentieth century.

On other imperial fronts,

the Roman Church has anointed herself "empress" over the Five Patriarchates.

This self-promotion reached an audacious zenith with her self-coronation

as the "Catholic Church,"

as if she alone were the ancient Church

founded by Jesus.

In historical fact,

the Roman Catholic Church, founded 1054,

continues in a state of separation from the universal Church by its own hand through a papal bull of

excommunication.

We have seen displays of Roman imperial pomp and majesty

in living memory.

Indeed,

the Roman Pontiff has been the only bishop in the history of the Church of Christ

to

gather around him a secular empire

called the Papal States.

A vestige of this empire continues to be seen in the Vatican,

a glittering display of worldly glory,

over which the pope sits as head of state.